Meditation on the breath

Sit comfortably on your meditation cushion or chair. Adopt the meditation posture and focus for a few minutes on your breath. Remember, you don’t need to change your usual pattern of breathing; simply pay full attention to your breath as it enters and exits your nostrils, generating the strong determination to concentrate on your breath, without allowing yourself to become distracted by anything whatsoever, internal or external. Again, press the pause button on your CD player while you do this meditation, and when you are ready to resume, press play button.

Motivation

Next you need to generate a positive motivation for doing this session, but first, since through the meditation on the breath you’ve made some space in your mind, look into your mind and ask yourself, “Why am I doing this course? Why am I studying this topic?”

If you find that your motivation is one of simply wanting to benefit this life, a motivation that’s concerned with the happiness and comfort of only this life—perhaps your motivation is simply to accumulate knowledge; perhaps you are doing this course because one of your friends has done it; there can be all kinds of worldly motivation—if you find that your motivation is, in fact, a worldly one, you should know that this is the actual cause of suffering, not a cause of happiness.

When we are motivated by impulses simply seeking happiness of this life, these impulses leave negative imprints on our consciousness, and at some future time, these imprints will ripen into experiences of suffering, problems, unhappiness. When we experience suffering, problems and unhappiness, we need to know that we are having that experience because of negative imprints that we ourselves, nobody else, placed on our consciousness at some previous time are ripening.

Now that we understand the karmic evolution of happiness and suffering according to the teachings of the Dharma, we need to ensure that we stop placing negative imprints on our consciousness and put positive ones onto it instead. Since placing negative imprints comes naturally, if we don’t think about motivation and just act as we normally do, we’ll certainly be placing negative imprints on our consciousness, because all our actions of mind, speech and body will be coming from motivations based upon the three poisonous minds of ignorance, attachment and aversion.

We need to consciously generate a positive motivation. It’s very important for you to be able to look into your mind and recognize whether your motivation for doing whatever it is that you’re doing is coming from a positive or a negative root. If it’s coming from a negative root, you have to abandon that motivation intentionally and replace it with a positive one, at least intellectually, as artificial as that might seem.

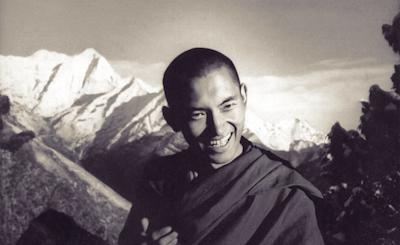

I remember that after my first Kopan meditation course, way back in 1972, I had an interview with Lama Zopa Rinpoche. It was one of the first times that I’d spoken to him one-on-one. And I said, “Rinpoche, intellectually, I think I want to work for happiness of all sentient beings, but if I really look into my heart, the motivation that’s really there is I want happiness for myself alone.” So Rinpoche laughed and said, “Well, that might be true, but if you don’t start with the words, where is a spontaneous, genuine motivation going to come from?”

As you become more and more familiar with the words, as you say the words again and again, as you study the subject, as you study the Dharma, more and more deeply, gradually you become more familiar with the meaning of the words, and gradually your motivation becomes more pure. Of course, we have to do other practices as well—practices to purify our mind in order to remove hindrances to spiritual development; practices to create merit in order to make our mind more fertile, or receptive, for the growth of realizations—but it all starts with the words.

So, look into your mind, and if you find you have a negative motivation for studying this topic of death and rebirth, for taking the Discovering Buddhism program, you need to discard that motivation and replace it with a positive one.

As I mentioned in the previous session, there are three levels of positive motivation: doing something in order to avoid being reborn in the three lower realms and to experience happiness in cyclic existence, in particular, to get a better rebirth; doing something in order to gain complete liberation from all of cyclic existence; and doing something in order to reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings, which is the highest, most positive level of motivation, bodhicitta.

Therefore, generate bodhicitta motivation by thinking, “I am studying the teachings on death and rebirth in order to reach enlightenment for the sole purpose of enlightening all sentient beings,” and having thought that, think about the meaning of these words for a moment or two.

Impermanence

Now I’d like to say a little about impermanence. In his book Illuminating the Path to Enlightenment, His Holiness the Dalai Lama introduces impermanence in context of transforming the mind, where he says that one of the ways we know that we can transform the mind is because of impermanence, that all things and events are subject to transformation and change. Then he goes on to say that the transient and impermanent nature of reality is not to be understood in terms of something coming into being, remaining for a while and then ceasing to exist. That is gross impermanence and is not the meaning of impermanence at the subtle level.

Subtle impermanence, which is the more important of the two, refers to the fact that the moment things and events come into existence, they are already impermanent in nature; the moment they arise, the process of their disintegration has already begun. When something comes into being from its causes and conditions, the seed of its cessation is born along with it. It is not that something comes into being and then a third factor or condition causes its disintegration. That is not how to understand impermanence. Impermanence means that as soon as something comes into being, it has already started to decay.9

Of course, the whole point is that this applies to us. The moment we are conceived, the process of our disintegration has begun. The problem is that we don’t feel the change that’s occurring within us every fraction of a second.

In The Wish-fulfilling Golden Sun, Lama Zopa Rinpoche paraphrases the great Kagyü Lama Gampopa’s Jewel Ornament of Liberation, when he says,

This vessel-like world which existed at an earlier moment does not do so at a later one. That it seems to continue in the same way is because something else similar arises, like the stream of a waterfall.10

In other words, as one moment is followed by the next, phenomena appear very similar, and our mind deceives us into thinking that they haven’t really changed, that they’ve remained the same. But of course, we know, and modern science has clearly shown, that everything is composed of molecules and atoms, and atoms are made up of nuclei and electrons and whatever else is in there, and they’re in a constant state of flux, nothing remaining still for the shortest fraction of a second.

In the Jewel Ornament, Gampopa introduces the section on impermanence with a quote from the Buddha, who simply said, “O monks! All composite phenomena are impermanent.” And in answer to the question that Gampopa poses himself, “In what way are they impermanent?” he quotes the Buddha again, from the text, the Verses Spoken Intentionally, saying,11

The result of all accumulation is dispersion.

The result of construction is falling.

All who meet together separate.

The end of life is death.12

Gampopa then goes on to classify impermanence in an interesting way: impermanence of the outer world, which is classified into gross and subtle impermanence, and impermanence of the inner sentient beings, which is classified into impermanence of others and impermanence of oneself.

Gross impermanence of the outer world is described by Gampopa as the end of the world, the end of the universe; ultimately, everything will be destroyed, and since the whole world will eventually end, what need is there to mention the things within it, especially us. We can also consider gross impermanence to mean the eventual disintegration of buildings, houses and so forth.

Subtle impermanence of the outer world can be seen in the changing of the seasons, the rising and setting of the sun and moon, and the vanishing of the instant moment. The seasons change before our eyes—spring turns into summer, summer into autumn, autumn into winter, and winter back into spring—but we don’t use what we see to benefit ourselves spiritually.

Every day the sun comes up, the sun goes down; the moon comes up, the moon goes down; by day it’s light, the night is dark—but again, we don’t think about these changes in a spiritually constructive way.

The third example of subtle impermanence in the outer world, the vanishing of the instant moment, is what Lama Zopa Rinpoche quoted before: the first moment of this world does not exist in the second moment, but since each moment is similar, we are fooled into perceiving them to be the same, like the flowing of the river.

Gampopa then goes on to talk about the impermanence of the inner sentient beings. When he says “inner,” I think he’s referring to sentient beings as being within the outer world, as being contained by the outer world. Sometimes Tibetan Buddhism uses the terms “the container” and “the contained.” The outer world is the container and what it contains is sentient beings. Therefore, sentient beings are called inner; they are contained within the outer world. So here we contemplate the impermanence of others and the impermanence of ourselves.

When contemplating the impermanence of others, we simply have to think how the sentient beings in the three worlds are impermanent. And again, Gampopa quotes the Buddha, who said simply, “The three worlds are as impermanent as autumn clouds.”13 The three worlds here are the realm of desire, the realm of form and the realm of formlessness. So it’s within these three realms that all samsaric sentient beings exist, and all are as impermanent as autumn clouds. Think about this image, although I’m not sure why it has to be autumn. Perhaps autumn clouds are more evanescent than the heavy, dark clouds of the summer monsoon. But we know how insubstantial clouds are, how quickly they come and go. Our world, our solid earth, the granite mountains we think are so stable are just as transient as clouds in the sky. It’s just that our limited perspective prevents us from realizing it.

Of course, it doesn’t take a buddha to realize this. Even Shakespeare, in As You Like It, said,

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women are merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts.

He’s describing us in cyclic existence. We enter into a life, we play that part and we exit. We get reborn, another entrance, another part, another exit; and there’s never an end to the encores. Until we get ourselves out of cyclic existence, off this great samsaric stage, we’ll always be playing one suffering part after another.

Echoing the Buddha and Shakespeare, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, also elaborated on this theme when he said,14

The realms of the cycle of existence are impermanent, like autumn clouds. The coming and going of sentient beings can be understood as scenes in a drama. The way sentient beings are born and die is similar to the way characters come on and off the stage. Because of this impermanence, we have no lasting security. Today, we are fortunate to live as human beings. Compared to animals and those living in hell, human life is very precious. But even though we regard it as precious, life finally concludes with death. Reflecting on the whole process of human existence from beginning to end, we find there is no lasting happiness and no security.

Gampopa then goes on to talk about contemplating the impermanence of oneself. He says we have to go to another life without choice, and we can understand this in two ways: by investigating impermanence within ourselves and by applying others’ impermanence to ourselves.

When it comes to investigating impermanence within oneself, there are four different ways of meditating: on death, on the characteristics of death, on the exhaustion of life, and on separation.

To meditate on death, we should think, “I myself cannot stay long in this world and will have to go to the next life.” Contemplate this. So, this is a topic for analytical meditation, and when studying impermanence, death and rebirth—actually, when studying any of the lamrim topics—analytical meditation is a crucial tool. At the beginning of these sessions we’ve done a short meditation on the breath and, as I mentioned at the end of the last session, that kind of meditation, where we try to concentrate, or focus, our mind single-pointedly on a particular object, is called placement meditation and is one of the two main types of meditation, placement and analytical.

The point about analytical meditation—where we bring to bear our powers of logical deduction onto a particular topic and dissect it to see whether it’s true or false and how it relates to our life—is not simply to arrive at a clear intellectual understanding of the subject, although that’s an important start, but to get realization of it. Realization is the deepest form of wisdom; here, correct understanding completely replaces ignorance, and realization of a particular topic comes about through analytical meditation on it in association with purification, creation of merit and prayer to the guru as one with the meditational deity. This last bit might not mean much to you at the moment, but file it away for now and come back to it when you have done more study.

Anyway, when doing these various meditations on impermanence and death, you have to employ whatever powers of logical deduction that you have. For instance, when contemplating a phrase such as, “I myself cannot stay long in this world and will have to go to the next life,” you need to understand the deep meaning of those words and use that understanding to change your life for the better, to make whatever time you have left positive, constructive, to make every moment you have left another step closer to not just your own enlightenment but that of all sentient beings. That is your ultimate aim. The only reason you want to become enlightened is to enlighten all other sentient beings.

The next contemplation when investigating impermanence within oneself, that on the characteristics of death, is to think, “My life ends, this breath ceases, this body becomes a corpse, and this mind has to wander in different places.” This is another topic to contemplate, to think deeply about.

When we meditate on the exhaustion of life, we think, “From last year until now, one year has passed, and by that amount my life has become shorter. From last month to this, one month has passed and my life is that much shorter. From yesterday to today is one day, and by this much my life is shorter. The moment that just passed right now is the passing of one moment. By that measure, my life is shorter.”

Then Gampopa quotes the great bodhisattva Shantideva:15

Definitely remaining neither day nor night,

Life is always slipping by

And never getting any longer,

Why will death not come to one like me?

We need to think deeply about what these great masters teach from their own experience.

Finally, we meditate on separation by thinking, “Right now, whatever I have—my relatives and wealth, this body and so forth that I cherish so much—none of this can accompany me forever. One day soon I will have to separate from them.” Contemplate that.

Again he quotes Shantideva,16

Up until now I did not understand

That I would have to leave all things behind.

There’s another way of investigating impermanence within oneself—the three roots, the nine reasons and the three determinations—which I’ll go into in the fourth session.

The purpose and importance of the teaching on impermanence and death

What’s the purpose of the teaching on impermanence and death and why is it important? Well, first of all, the first teaching that the Buddha ever gave was on impermanence, and it was also his last. After the Buddha attained enlightenment in Bodhgaya, he didn’t teach at first, but a few weeks later came to Sarnath, where he was persuaded to give his first teaching, which was on the Four Noble Truths: the truths of suffering, the cause of suffering, the cessation of suffering and the path to the cessation of suffering. Each of these Four Noble Truths has four aspects, and the first aspect of the First Noble Truth, the truth of suffering, is impermanence. That was the first thing he taught.

Then, some forty or more years later, just before the Buddha’s final parinirvana, just before he passed away, the very last teaching he gave was on impermanence. He said,17

All conditioned phenomena are impermanent.

This is the last teaching of the tathagata.

So the fact that the Buddha’s first and last teaching was on impermanence is extremely significant.

To quote Lama Tsongkhapa again from the same text that I quoted at the beginning, The Foundation of All Good Qualities, he says,

Understanding that the precious freedom of this rebirth is found only once,

Is greatly meaningful and difficult to find again,

Please bless me to generate the mind that unceasingly,

Day and night, takes its essence.

Having been cycling through the six realms of samsara since beginningless time, spending most of that time in the three lower realms, this time we have received a perfect human rebirth. This time we have found an upper rebirth, and not just an ordinary upper rebirth but a human rebirth, and not just an ordinary human rebirth, but a perfect human rebirth, which has the eight freedoms and ten richnesses that give us every opportunity to work for the enlightenment of all sentient beings, which is the purpose of having being born human at this time, in this life.

However, we spend this precious human rebirth largely in meaningless activity, and in order to motivate ourselves, to persuade ourselves, as Lama Zopa Rinpoche puts it, to extract the essence from this perfect human rebirth, we need to meditate again and again on how precious this life is, how much we can do with it, how it will be extremely difficult to find again, and how short it is: how it’s definitely going to end and how it’s ending every moment. In other words, we need to meditate on impermanence and death in order to get it through our thick skulls that every moment of this precious human rebirth that is wasted is lost forever, an opportunity almost impossible to find again.

And, as Lama Tsongkhapa says, we need to generate the mind that unceasingly, day and night, takes the essence from this perfect human rebirth, and one of the main ways that we generate such a mind is by meditating on impermanence and death.

With respect to the purpose of this meditation, His Holiness the Dalai Lama says,18

The significance of meditating on impermanence and death is not just to terrify yourself; there is no point in simply making yourself afraid of death. The purpose of meditating on impermanence and death is to remind you of the preciousness of the opportunities that exist for you in life as a human being. Reminding yourself that death is inevitable, its time unpredictable and when it happens only spiritual practice is of benefit gives you a sense of urgency and enables you to truly appreciate the value of your human existence and your potential to fulfill the highest of spiritual aspirations. If you can develop this profound appreciation, you will treat every single day as extremely precious.

He then goes on to say,

As spiritual practitioners it is very important for us to constantly familiarize our thoughts and emotions to the idea of death so that it does not arrive as something completely unexpected. We need to accept death as part of our lives. This kind of attitude is much healthier than simply trying not to think or talk about death.

In some ways, it might be better not to think, as we do, that we’re living but that we’re dying. If we acknowledge that from the very moment of conception we have been rushing towards our eventual demise, we’ll see that actually, although we call it “living,” we’re dying. This recognition gives us a better perspective on what we call life.

In some ways, also, death is the most important part of life and we should have a sense of urgency about its imminence, because not only is death the end of this precious opportunity that we have but we also have to realize what’s likely to come after death. We’re not only heading towards death, we’re also approaching our next life. So what’s that going to be like?

At the time of death, there are only two directions that the mind can take. One is to go down into the lower realms; the other is to go up into the upper realms. What is it that determines the direction that our mind will take? It’s karma; specifically, throwing karma—the karmic imprint that arises at the moment of death, the moment our mind leaves our body, and throws us into our next life.

Since we know that negative karma is created by actions done out of ignorance, attachment and aversion and that almost every action we have ever done has stemmed from those roots, we can understand that our mind is replete with negative imprints and almost devoid of any positive ones. Therefore, the chances are very strongly in favor of a negative imprint arising at time of death.

This is probably not the right course to go into details of this topic, which is covered more fully in module on karma, but we have to understand that we’re in a very dangerous and serious situation. We have this precious life, it’s running out very quickly, we don’t know when death is actually going to occur, and if it occurs too soon, if it occurs before we’ve enough time to practice Dharma and purify all these negative imprints in our mind, if it occurs before we’ve the chance to create much merit, then it’s almost guaranteed that we are going to be reborn in the lower realms.

Life in the lower realms is fraught with the most unbearable sufferings. The worst sufferings are in the hell realms. Lighter than those but still unbearable are the sufferings of the hungry ghosts. And lighter than those but also unbearable are the sufferings of the animals. Lama Zopa Rinpoche has said that if we could really experience the mind of an animal, if we could really feel, if we could really understand what it’s like to be an animal for even thirty seconds, we’d get such a shock that we’d never sleep again. In other words, we’d spend every moment of the rest of our life practicing Dharma, purifying negativities, creating merit, in order to avoid having that experience. The experience of being an animal isn’t the worst of the lower realm experiences, but it’s still so bad.

We see animals all the time—domestic animals, wild animals, birds, fish, insects and so forth—but we only see their body, we don’t see their mind. We don’t understand what it’s like to be in that life form. And when we see them, we never think, “That could be me. The only thing between me and life as an animal is my breath.” The day we breathe out but don’t breathe in is the day we trade this precious human body for that of a cockroach, a snake, a caterpillar or something like that. We are totally oblivious to reality.

This meditation on impermanence and death is supposed to wake us up from this deep sleep of ignorance and shake us into an awareness of what is.

So, death really is the most important part of life because it’s like the final examination. It’s what happens at the time of death, how we handle death, that determines whether we get an upper rebirth, another perfect human rebirth where we can continue our Dharma practice, or get reborn into the horrible experiences of the three lower realms, from which it’s extremely difficult to escape.

If we become friends with death, if we become familiar with death, if we are able to control our death, then we’ll have a much better chance of finding a good rebirth. If we don’t, then as we die, our subconscious, or our unconscious, mind will take over, and we’ll have no control, and since that mind is full of negative imprints, then we will be thrown into the lower realms and we will have wasted this precious opportunity that we now have.

In the Thirty-seven Practices of a Bodhisattva, the great teacher Togme Zangpo said,19

Loved ones who have long kept company will part;

Wealth created with difficulty will be left behind;

Consciousness, the guest, will leave the guesthouse of the body;

Let go of this life;

This is the practice of bodhisattvas.

So although death is natural, everybody dies, we know we’re going to die, we know that our mind is but a guest in our body, our mind is simply passing through this life, like a tourist visiting a particular country, even though we know all these things, we still have an instinctive fear of death; all beings have an instinctive fear of death and try to protect their lives.

Fear

In some ways, for a lot of us brought up and educated in the modern world, it’s kind of illogical to fear death, because most of us are brought up to believe that at death, everything stops; that there is no life beyond this one; that when we die, it’s all over. This is the so-called scientific point of view. So from that point of view, those who have very difficult lives, very suffering lives, should welcome death, but even people who have many, many problems in their life don’t welcome death; they try to stay alive.

Why, then, do we have an instinctive fear of death? It could be because we’ve been dying since beginningless time—there’s no number to the deaths that we’ve already experienced—and in the vast majority of cases, as unwanted and terrifying as those deaths have been, the dreadful suffering in the lower realms that has followed has been truly horrifying. Therefore, our mind contains a great depth of experience of death leading to unbearable suffering, and it’s probably a forgotten memory of the suffering that follows death that instinctively makes us fear it. Even though it’s natural, even though it might be the end of a suffering life, we still don’t want it to come.

Some people think that fear is always a bad thing and that being motivated by fear is something to be avoided. But Tibet’s great yogi, Milarepa said,20

Through fear for death, I fled to the mountains, where I realized the nature of the mind. Now death holds no fears for me.

In Milarepa’s case, then, fear of death was the catalyst that led him to practice Dharma and reach enlightenment. How bad was that?

In other words, there are positive fear and negative fear. Negative fear doesn’t help; negative fear simply makes us afraid and doesn’t lead to beneficial activity. Positive fear protects us. For example, we don’t put our hand in a fire because we are afraid of getting burnt. There’s nothing wrong with that. We look both ways before crossing a busy road because we’re afraid of getting hit by a bus. There’s nothing wrong with that either. That’s positive fear; it’s constructive. So in itself, there’s nothing wrong with fear; it depends whether it’s positive or negative.

In the Wish-fulfilling Golden Sun, Lama Zopa Rinpoche quotes one of the previous Karmapas, who said,

Why should I be afraid of death? Because when the Lord of Death comes, it is difficult for the mind to be happy.21

First of all, in this quote, the “Lord of Death”—there’s no actual Lord of Death, like some Grim Reaper waiting with a big scythe to lop off our heads when our number’s up. Rather, it’s a personification of death, to give death a face, to allow us somehow to able to relate a little more to death. When you look at paintings of what’s called the Wheel of Life—in Tibetan Buddhism there’s a particular depiction of the six realms of cyclic existence, the twelve links of dependent origination, the hub of the wheel showing ignorance, attachment and aversion, the principal delusions driving the whole thing?this Wheel of Life is held in the fangs and claws of a terrible looking monster, Yama, the Lord of Death: this is to show that all beings living in cyclic existence are subject to death and rebirth. So the Lord of Death here isn’t some nasty being out to end our life.

“When death comes, it is difficult for the mind to be happy” is important because we know from our own experience how our mind tends to continue for a while in the state that it’s in. For example, when we get angry we can’t just switch it off; that anger reverberates in our mind, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days; usually for a while. When we are depressed, when we are unhappy, people might say to us, “Snap out of it,” but it’s easier said than done. So, if we’re unhappy at the time of death, if we’re frightened, if we’re terrified, if we’re worried, if we’re scared, when we die, our mind will tend to continue in that state and we’ll be reborn as a frightened, terrified being, like a mouse, for example.

When you look at a mouse, it’s always running here and there, looking over its shoulder, scared of any sound, any movement. That’s the sort of result that can come from being scared, unhappy and afraid at the time of death. It’s much better to be able to die in a happy frame of mind, because the mind that dies happy will be reborn happy.

After mentioning this quotation, Rinpoche then says,

I am greatly ignorant in being unafraid of death. This lack of fear results from not understanding the suffering of the death process itself or the suffering of my future lives. After death my ignorant mind will continuously suffer in the cycle of the twelve dependent links. In one month, one day, even in an hour, I create more negative than virtuous karma and have been doing so since beginningless time, in all my previous lives.

This was what I was saying before: we must realize the desperate situation we’re in and without wasting any more time, practice Dharma as strongly as we can, from this very moment on.

Rinpoche then goes on,

Unless I break my chain of bondage to the cycle of the twelve dependent links, I shall soon be reborn in one of the three lower realms. For these reasons, I should start practicing Dharma immediately, without being lazy.

Guru Shakyamuni Buddha said,

It is unsure whether tomorrow or the next life will come first. Therefore, it is more worthwhile and wise to be prepared for the future life than for tomorrow.

That’s a very interesting thought, too: since it’s not sure whether or not we’ll be alive tomorrow but absolutely definite that we’ll experience the next life, it’s much more logical to be more prepared for the next life than for tomorrow.

The way to prepare for the next life is to practice Dharma as much as possible in this life and to have a good death. There are three levels of good death. Lama Zopa Rinpoche said,22

For the purest Dharma practitioners, dying is like going back home, like going on a picnic. They look forward to death and die very peacefully, their mind happy, relaxed and worry-free. Even if they’re surrounded by relatives and friends weeping and suffering, the most accomplished practitioners die with great joy, as if going on holiday, because they’ve spent their life in meditation, constantly remembering impermanence and death, creating merit, purifying negativities and not creating any more. Intermediate level practitioners also die happily, without worry, even if they don’t look forward to it like the best practitioners do. The lowest level practitioners, who have also created much merit during life, aren’t bothered or upset by death. Unlike ordinary people, they die without fear or regret.

If we, too, can at least die without regret, without thinking of how much we wasted our life, of all the missed opportunities, that’s still OK. Nevertheless, we should strive to be better; we should strive to be confident of not being reborn in the three lower realms, like the intermediate-level practitioner, or, of course, to be one of those practitioners who looks forward to death.

Meditation

Now that you’ve thought some more about impermanence and death, please go back to Meditation 1 and practice it again before going on to the third teaching session.

Dedication

Let’s again dedicate the merits we created during this session. We began by generating bodhicitta motivation, the highest possible motivation, and the action we did, studying the Buddha’s teachings on impermanence and death, is certainly harmonious with that motivation. We looked at impermanence; we looked at the importance and purpose of the teaching; we thought about positive and negative fear; and we mentioned the three positive ways that we could feel at the time of death. So, all in all, we’ve created a great deal of merit and we should dedicate this before it’s destroyed by anger or wrong views, ignorant views such as thinking there are no past and future lives, that there’s no such thing as karma, that the Three Jewels—Buddha, Dharma and Sangha—are not a worthwhile refuge, things like that, that are contrary to reality.

We can do a simple dedication, thinking, “Because of all these merits, may all sentient beings quickly reach enlightenment.”

Thank you very much.

9 Illuminating the Path, pp. 7-8. [Return to text]

10 Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun, p. 51; Jewel Ornament of Liberation, p. 85. [Return to text]

11 Jewel Ornament of Liberation, p. 83.[Return to text]

12 This text, a compilation of the Buddha’s sayings, has been published in English as The Tibetan Dhammapada; the first chapter is a collection of aphorisms on impermanence. [Return to text]

13 A fuller version of this quote is given in the Great Treatise, p. 151, and attributed by Lama Tsongkhapa to the Extensive Sport Sutra: “The three worlds are impermanent like an autumn cloud. The birth and death of beings is like watching a dance. The passage of life is like lightning in the sky; it moves quickly, like a waterfall.” [Return to text]

14 Joy of Living and Dying in Peace, p. xvii. [Return to text]

15 Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, p. 28, 2:39. [Return to text]

16 Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, p. 27, 2:34. [Return to text]

17 Quoted in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, p. 344. [Return to text]

18 Illuminating the Path, pp. 78-9. [Return to text]

19 Transforming the Heart, pp. 67-84. [Return to text]

20 Also quoted in Liberation, p.342. [Return to text]

21 Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun, p. 52. [Return to text]

22 Sixth Kopan Meditation Course, April 1974, unpublished transcript. [Return to text]

Sources for these publications can be found on the References page.