Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa, 17 October 198211

Geoff Jukes: Lama, how did you first get involved in teaching Dharma to Western people? How did this come to be?

I began teaching Westerners in the late 1960s. At that time I was based at the Tibetan refugee camp of Buxa Duar, West Bengal, India, where I’d lived since 1959, following the Chinese invasion of Tibet. Lama Zopa Rinpoche was one of my students there and from his time in Tibet had a connection with the monks of Samten Chöling Monastery at Ghoom, near Darjeeling. They invited us to come there for a holiday, which was the first one I’d had since arriving at the Buxa “concentration camp.”

So there we were at the monastery, and one morning a monk knocked at our door and said, “Lama Zopa’s friend has come to see him.” It was Zina Rachevsky, a Russian American woman, who was supposed to be a princess or something.

She said that she’d come to the East seeking peace and liberation, and asked me how they could be found. I was kind of shocked because I’d never expected Westerners to be interested in liberation or enlightenment. For me, that was a first. I thought, “This is something strange but very special.” Of course, I did have some idea of what Westerners were, but obviously it was a Tibetan projection! So, despite my surprise I thought I should check to see if she was really sincere or not.

I started to answer her questions as best I could, according to my ability, but after an hour she said she had to go back to where she was staying in Darjeeling, about thirty minutes away by jeep. However, as she was leaving she asked, “Can I come back tomorrow?” I said, “All right.”

So she came back at the same time the next day and again asked various questions, which I tried to answer. Somehow she got some kind of message from the teachings I gave her. She became very enthusiastic and again asked if she could come back the following day.

In this way she came for teachings every day for a week or more. Finally, she said, “It’s very expensive for me to come here every day by jeep. Could you please come to stay at my place and give me teachings there?”

At first I was a little bit scared; I didn’t quite know what to make of this Western lady. But her sincerity made me believe in her and encouraged me to go, so I said OK, and Lama Zopa and I moved to her house. She lived in the main cottage and we stayed in a small hut outside, in the garden, quite separate from where she lived.

We gave her lessons every morning, from about nine or ten o’clock until midday, which she liked very much, and finished up spending about nine months there; quite a long time. Then she had visa problems and got into trouble with the Indian police.

She was a very strong character, an unusually strong woman, and told the police that they were pigs and should stay away from her place. This rather annoyed them and they tried to hassle her but there wasn’t much they could do until they decided to label her a Russian spy. Then they put a lot of pressure on her and kicked her out of Darjeeling.

She finished up having to leave India and went to Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. She wanted Lama Zopa and me to go with her to continue teaching her Dharma and meditation, but we needed His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s permission to travel and some kind of refugee document from the Indian government. It took about a year to organize all that, but we finally got His Holiness’s permission and an Identity Certificate through the Tibetan Bureau in New Delhi, and we were ready to go.

Zina came up from Ceylon to meet us in New Delhi, having in the meantime decided to become a nun. I thought that was a good idea but since, according to the Vinaya, novice ordination requires the participation of at least four monks in addition to the preceptor, Lama Zopa and I couldn’t do it ourselves, so we went to Dharamsala to ask His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He couldn’t do it either but arranged for some other lamas to ordain her, and in that way Zina became a nun.

For some reason I felt uneasy about going to Ceylon so I suggested to Zina that we go to Nepal instead. It was close to Tibet and beautiful, peaceful and quiet. Environment is very important and I thought that since Zina was now a nun she needed to be where she could lead a simple life. Taking ordination alone is not enough. After leaving life in the big samsara you need time to adjust to life as a monk or nun, and your surroundings are very important in this.

Zina agreed, so the three of us went to Nepal. After a while her friends started coming to us for teachings and after we’d been in Nepal for a couple of years, we moved to Kopan. She kept requesting that we give a group meditation course, so in March 1971 Lama Zopa finally gave the first Kopan course, and that was really the beginning of our involvement in the Western world.

So you can see that we started off slowly. We thought teaching Dharma to Westerners would be beneficial but we didn’t hurriedly push; it was a gradual evolution. We took our time observing and checking intensively whether Buddhism worked for the Western mind or not. When we were confident that it did, we offered our first course. About twenty people attended the first couple of courses and then the numbers kept doubling until about two hundred and fifty people came to the sixth. After that it leveled out at around two hundred.

So that’s how we started teaching Dharma to Westerners.

Did you find, Lama, any particular difficulties in the approach you had to make to teach Western people? Did you find anything, any specific problems there that were not usual in Tibet?

Yes, well, the first thing I had to understand was how to present Buddhism to Westerners who were new to it; how to approach the Western mind with these new ideas. You can’t teach Westerners the way we teach Tibetans. We have to start slowly; it’s a gradual process. Also, Westerners are going to expect something concrete, something solid; something they can easily get their minds around.

Also, traditional teachings use lots of examples, like from India perhaps two thousand years ago; certain things that don’t work for the Western mind. We have to update these so that the examples we use mean something to their mind and accord with their experience. And the statements we make should be concrete and given in a clean-clear manner.

Additionally, the Tibetan system of teaching relies on the use of many scriptural quotations: “In this particular text, Nagarjuna said this, this, this and this.” It’s similar to the way Christians might quote the name of the book, chapter and verse from the Bible: “See John, chapter this, verse that.” Those historical quotations are not necessarily concrete statements, not something straight and structured, so they don’t always work for the Western mind.

Therefore, we have to try different ways of approach. Of course, we don’t change the characteristics of the pure Dharma, but what we have to think about is the way we teach it, how to put it into the Western mind, how to open the Western mind into that space. We have to give all this a lot of thought before teaching; how to get the true Dharma into the Western brain. For me, it takes quite a bit of energy and a lot of sympathetic thinking to decide how to present the various Dharma subjects to Western students.

At first, we had to kind of experiment. For example, when teaching Westerners refuge in the Buddhadharma, we have to explain it more scientifically than we do when teaching it Tibetan style. And it’s the same with karma, which is an incredible subject, a huge subject. Karma can be taught a hundred different ways, but when teaching it to Westerners, it also has to be presented scientifically and explained with reference to everyday life rather than philosophically. They will comprehend it more easily when it’s taught that way.

There are many aspects of Buddhist philosophy that contradict Western philosophy. Certain things in Buddhism have nothing to do with Western philosophy. It becomes a new dream philosophy for them. So until Western students have oriented themselves to Buddhist philosophy, you can’t put the reality of karma into that frame. Therefore, for me to teach karma to Westerners, I have to go beyond the Buddhist philosophical frame myself, extract the nuclear essence from traditional teachings on karma and put that into the Western mind.

So it’s not all that easy to bring Dharma to Western people, especially when it comes to teaching the philosophical way, because they’re not oriented to philosophical understanding. They know nothing about Buddhist philosophy, so if I start using philosophical logic, they’re going to say, “What?” They think Eastern philosophy is the opposite of Western. Instead of being helpful for them, they say, “No. We think this way; you think that way. Your logic asserts that something is existent because of this. We say it’s nonexistent because of that.” So that poses quite a challenge for me!

Furthermore, I should never hang on to any kind of fixed idea. Every time I teach I have to ask myself what kind of people are here? What’s their background? Is it religious or nonreligious, philosophical, scientific or non-scientific? I try to get as much information on those attending as I can and then try to relate to them accordingly. It takes quite a bit of effort.

Fortunately, however, Buddhism does contain the kind of skillful means that allows us to deal with all kinds of human beings. The Buddha taught us how to go beyond limited concepts and philosophies as long as we understand the essential aspects of the teachings and don’t lose them. In that case, I don’t care what the philosophical structure is. It’s more important that those who teach Tibetan Buddhism in the West are more concerned with the essence of the teachings, not only the philosophy.

It’s also good that people teaching Westerners relate more to Western philosophy, psychology and ways of thinking. That way, the teachings they present become very acceptable, and students can understand and comprehend them easily. Otherwise there’s going to be a disconnect between the teacher’s and the students’ minds and no way for the teachings to transform, or help, the students’ minds.

Anyway, it’s very important that we convey the essential aspects of Buddhism rather than just always follow the system. Following the system is good once the students have been established on the path but not if they are just beginners. Since the teachings don’t yet exist in their mind, you’re just talking about some Shangri-la with which they’re not familiar.

What then would you say is the essence of Buddhism? What would you describe as the essence of Buddhism?

I consider things like the four noble truths, the noble eightfold path, the three principal aspects of the path to enlightenment—renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness—the four immeasurables and so forth to be the essence of Buddhism. Those topics are so scientific, so understandable, so logical. Nobody can deny their truth. Those teachings are very practical.

But we should not only explain them. We should also teach the students how to practice them. In order to solve modern Western problems they have to meditate on the teachings. If we only present them as some kind of miracle or magic, they won’t be helpful; they won’t solve the students’ problems.

So therefore, teaching the essence of Buddhism is such a clean-clear way of presenting the Buddhadharma to everybody, irrespective of culture, religious philosophy and so forth, without hurting their feelings. The essence of Buddhism is just right for everybody, religious or nonreligious. That is the beauty of Buddhism. There’s no contradiction.

Do you see, Lama, a form of Western Buddhism evolving in the way that Indian Buddhism changed when it moved into other cultures such as Tibet, China, Japan, Thailand and so forth? Do you see Tibetan Buddhism being readily absorbed into a Western environment in the way that Indian Buddhism was absorbed into Tibetan culture?

Well, I tell you, one of my great pleasures in life is first teaching the essence of Buddhism and then seeing how we can put it into a Western cultural environment. Why is that? I truly believe if somebody understands the essence of the universal teaching and practices that, it is much more powerful than another person interpreting the teaching as merely cultural and then taking that as part of their own culture. That’s a sloppy mind. Then that person’s practice becomes a routine, simply a custom.

I find it is most beneficial if both student and teacher come together without expectation, although when new people contact Buddhadharma for the first time, I expect them not to accept it. Then I have to fight their wrong conceptions, their wrong ways of thinking about life, success and pleasure. I have to bring all these things into the conversation and say, “That’s how you think? That’s wrong. You need to think this way. . . .” So that’s the challenge.

Nevertheless, I think many Westerners become Buddhists the right way: through understanding rather than blind faith. Those who do are very fortunate. They might already have the intention of accepting Buddhism, but first they check out what these Buddhist monks are saying, what Buddhism offers them. They examine the teachings first and don’t just expect to gain something that they assume is already acceptable. So that’s the beauty of how Westerners become Buddhists. They take it seriously and base their decision on a comprehensible wisdom experience rather than some kind of cultural habit. For me, that’s a much better way of becoming a Buddhist than the way people who are born into Buddhist societies and just accept their culture with a sloppy mind: “Buddhism is my home, so I can just sit back here very comfortably.”

However, I don’t believe Buddhism should be comfortable. Buddhism likes to shake up people’s darkness of ignorance, darkness of craving desire, people’s attachment. As far as life is concerned, Buddhism is not comfortable!

So I think many Westerners become Buddhists because they find it helps them. They experience benefit. They don’t become Buddhists because they like the ideas of Buddhist philosophy. They don’t do that, and I don’t like it, either. People try Buddhist meditation and find that it helps them eliminate their confusion and dissatisfaction. That’s the way they decide to become Buddhists and I truly believe that that is a wonderful way to make that decision.

Even in Shakyamuni Buddha’s time, that was the way people became Buddhists. In those days people were already spiritually oriented, and the first thing he taught was the four noble truths. People actualized those truths for themselves and therefore began to follow the Buddha’s path. I think it’s very good that, in the same way, skeptical Westerners try out the teachings for themselves to see if, in their experience, they are helpful or not. When they get a taste of the benefit, they become Buddhist. That impresses me a lot. That’s a very good way to become Buddhist.

With respect to those people who have experienced Tibetan Buddhism for a long time, who’ve received teachings for perhaps ten or twelve years and found them very helpful, they remain Buddhist as a result of their experience, not because it has become a sort of custom for them. Customs are not important. If you try to transplant Tibetan customs into the Western world, it’s not going to work. Anyway, Tibetan customs don’t offer a true picture of Buddhism.

Looking at the big picture, we see how Buddhism went from India to China, Japan, Tibet and so forth and took different forms as it adapted to the local culture, but Tibetan culture, for example, can never become, say, Italian culture. Similarly, I’ve seen some students who’ve had a taste of Buddhism try to become Tibetan. How can that be possible? It isn’t. They’re just joking. It’s better that they become Buddha or Dharma. That’s more realistic; that’s possible.

In the long run, when Tibetan teachers come to the West and the Dharma is established there, we’re going to see like Italian Buddha, Italian Dharma, Italian Sangha. We’re going to see European-style Buddhism. We’re not going to see Tibetan-style Buddhism take root in the West. And in terms of practice, there are certain Tibetan rituals that we do not need to bring to the West. Our emphasis should not be on ritual. That’s the same as trying to bring Tibetan culture to the West.

I truly believe that the most important thing is to understand Buddhist philosophy: understand the mind, understand how to approach enlightenment, understand how to attain liberation from misery. Those things are the essence of Buddhism and have to be actualized in daily life.

However, things like Buddhist ordination, such as the five precepts, are not local customs. Precepts have nothing to do with Tibetan culture. Wherever you go in the world, negative is negative, positive is positive, and protecting the mind from negativity is the essential thing.

But while the true essence of Buddhism doesn’t emphasize ritual, there are times where ritual can come into play, such as when we need to identify ourselves as certain transcendental archetypes in tantric practice. But at other times, no. That’s rubbish. The human mind is relative and conditioned; here in the West our lives are materialistically oriented. Even in the West we have different environments where people think differently, so Tibetan rituals are, for the most part, not going to work.

Take Europe, for example. If you were to describe today’s Europe to the Europeans of a hundred years ago, they’d think you were crazy. Even Europe has changed so much during that time. It’s similar with Tibetan culture. Tibetan culture is incredibly old and there’s no way you can import it to the West. So, when Tibetan teachers like myself come to the West, they should not expect Dharma students here to behave like Tibetan ones. That doesn’t mean Eastern students are better than Western ones. It just means that they behave differently. If a Tibetan teacher expects Western students to behave like Tibetan ones, he’s in for a shock! But while the teacher-student relationship is different, in essence it’s the same thing.

So while Western people are not oriented to Eastern philosophy and do not have a Buddhist frame of reference, the essence of the teachings can still touch their heart, and as a result they become Buddhist in a very correct way. If you see Buddhism as a cultural thing or as a local custom, it won’t give you any answers because you don’t get the essence.

Nevertheless, Buddhism coming to the West is very much the right thing. It is sorely needed as there is so much suffering here. People are materially well-off, but in a way that makes their mental anguish greater. Their monkey mind sees the physical comfort and gets restless, seeking better or more. In order to calm this boiling water mind down, we need powerful understanding and the nuclear energy of meditation.

The Western environment is really full-on. Everything is too strong, people are very sensitive, and Western life becomes sensitive, strong and concrete. Western ego conflict is so serious, so powerful. In other words, to generalize, desire in the Western environment is much more powerful than it is in the East. Anyway, in the East there aren’t that many desirable objects . . . I’m joking! Maybe. No, it’s not true.

What I mean is that the Western environment is set up in such a way that objects of desire are prominently displayed, and as a result the ego is so strong. In order to eliminate ego and desire, we need a powerful antidote to counteract our problems. Cultural rituals are not enough; playing cymbals is not enough. We need powerful meditation, powerful thinking in order to solve our problems.

Therefore, if your only orientation is toward Tibetan ritual, you just can’t solve your problems. It’s not a powerful enough instrument to play in the Western world. That’s my point. A Western environment demands strong meditation. That’s why I think Buddhism is so helpful for Western people. Delusion has really exploded in this twentieth century, so when you explain the meditational antidotes, problems get solved. This, I think, is Western people’s experience.

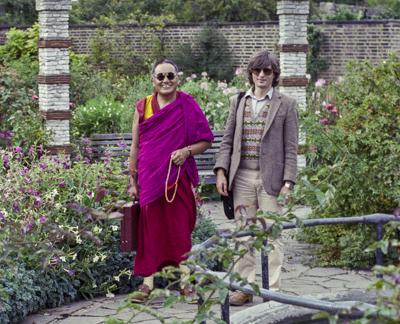

So, Lama, from the early beginnings you described, there are now more than thirty centers around the world that your teachings have inspired.12 Recently His Holiness the Dalai Lama visited three of your European centers. Does this have a special significance as far as you’re concerned?

Well, in the West there are many followers of Buddhism and our students have established many centers, and I feel that we have been somewhat successful in helping Western people with Buddhism. And Buddhism is not only for people who meditate. I think it has something for all of society, for the entire Western world. The ancient Tibetan religious culture is somehow a powerful reinforcement of all that, and His Holiness is its spiritual and political head. We believe that he is a great leader in the world, and someone who is very rare.

His Holiness coming to the West has cultural significance as far as society in general is concerned, but more than that, it ensures that Buddhism will be established in the various countries and that Dharma centers are not considered to be just some kind of trip. It does have cultural aspects, but it also involves sincere, serious work so that the Dharma will continuously benefit the Western world.

So that’s basically my understanding, but I really feel that His Holiness coming to Europe at this time is like a second Shakyamuni Buddha appearing on earth to stabilize the light of Dharma wisdom and show the path to liberation to all the people of Europe. With his blessing, all the Dharma teachers and students who have dedicated their lives to benefiting Western people will be successful and their wishes will be quickly fulfilled. That’s the meaning I take from it.

Bringing Dharma to the West is not an easy job. There are many misconceptions about Tibetan Buddhism in the West that need to be purified by offering a true picture of Buddhism instead. His Holiness is the light to purify all wrong views and also the sectarianism that exists within Buddhism itself. He represents not only all the Tibetan Buddhist traditions equally; he’s sort of the universal representative of all the world’s religions. Therefore, at this critical time, His Holiness’s presence is important for not only religious people but also nonreligious ones as well. He can make the entire world community harmonious.

When I listen to His Holiness’s lectures, his message of universal love and universal compassion, I hear him encouraging each of us to take universal responsibility to bring happiness to everybody on earth. Everybody can understand that message. And I hope the result will be that there is no more room for sectarianism: “My religion is better than other religions.” Buddhism teaches that every religion, every philosophy, contains good things for human development, for each individual’s needs. And that’s good enough.

In short, His Holiness the Dalai Lama coming to Europe at this time is an incredible blessing. I really feel it was something very unusual. And I think that Western people also felt there was some kind of incredible harmony and mutual understanding among the world community. This is the way to engender world peace, world harmony, world liberation. His Holiness teaches the best way to develop harmony both individually and universally. So bringing him to the West has been very important.

Thank you, Lama. Is there anything else that you would like to say, especially relating to the attitude of Western students?

Well, one thing is that, since our Western students have been lucky enough to encounter Mahayana Buddhism, the Great Vehicle, I would like them to have universal comprehension, a universal attitude. That is very important.

I feel that all of us have the problem of a narrow mind: “I’m Tibetan; you’re English.” English people identify their way; Tibetans identify theirs. We don’t have a global vision; we don’t have world community feeling. I feel that I’m part of the Tibetan community and don’t belong to the English one. That is not true. That kind of attitude is wrong. What I want is for all our centers to be sort of international in style; to have a feeling of universal brotherhood, universal sisterhood, rather than just “Lama Tzong Khapa Institute is an Italian center.”

This center is not only for Italians. Anybody can come here to use this facility, receive teachings and meditate. This building does not belong to Italy, does not belong to Lama Yeshe, does not belong to any particular person. It belongs to the world community. That’s the kind of attitude I’d like our students to have.

Also, for me, even though I have a small mind, I don’t have the idea that, “This is my home; this is my center.” No. This is not my possession. This center belongs to the world community, not me. I am just one monk. Why would I need such a big house for me?

Therefore, I would like the student community at all our centers to have the attitude that their center, including all the tables, chairs and everything else, belongs to the world community, not to them alone. I mean, in our prayers, we always say “all mother sentient beings,” but then our narrow mind makes divisions between them. That’s not good. We should have a broad view. Our centers are world centers, international centers, open to the world community. Students should not be sitting in their own little world, thinking, “This is our center, we’re good here. The rest of the world stinks.” Anybody should be able to come here.

By being open like this, we are practicing bodhicitta. Otherwise what? Otherwise it’s like you’re part of a married couple; you’re married to your center. Then you experience the same problems that a couple has. That attitude is wrong. We should think that the center belongs to anybody who comes here and present it that way. And it’s especially important that the center director be open in this way. If you’re open enough, there’s room for everybody.

Our problem is that we grasp at our own culture and our goals are quite narrow, and in today’s world that just doesn’t work. The world is changing rapidly and far from being negative, that’s a positive thing. It gives us the opportunity to put bodhisattva philosophy into action. That’s great, incredible. I mean, look at us sitting here. You, a London boy, and me, a Tibetan monk, now have the opportunity to communicate, to exchange ideas. It’s only relatively recently that we’ve been able to do this kind of thing.

Therefore, since the twentieth century has developed this way, it’s the right time, the right atmosphere, to put Buddhism into action. That means developing universal responsibility, taking responsibility for all universal living beings, for everybody on earth, and working for their benefit. We create a universal community, we identify ourselves as universal, and in that way we become universal. I think so.

Of course, sometimes this might make our ego feel uncomfortable, but then again, even when living in our own society we feel uncomfortable. So it’s very useful for Western Dharma students to feel that they are part of a world community.

Notes

11 An interview with Geoff Jukes, filmed by the Meridian Trust. Available on the DVD Bringing Dharma to the West, on the LYWA YouTube channel and from the Meridian Trust as Extracting the Essence. [Return to text]

12 In 2022 the FPMT comprised some 145 centers, study groups, projects and services in 36 countries. [Return to text]