At the outset I mentioned two ways of taking the bodhisattva vows. The first is the wishful way, wanting to develop the mind that wishes to help other sentient beings as much as possible, realizing that to help others in the best way you have to develop toward liberation as quickly as possible, and trying to maintain that motivation continuously in this, the next and all future lives. You have no doubt that this is the best way to go, but you may feel, with respect to actually practicing the bodhisattva path, that you cannot keep the sixty-four vows or engage in the extensive deeds right now. Think, "I shall do as much as I can, but I cannot take the full commitment at the moment." This way there is no heavy vow and you do what you can.

If you take the vows the second way, you think, "I shall keep the root and branch vows and actualize the six perfections as much as I possibly can from now until my death, forever." This is the sort of strong determination that you make.

Thus, there are two ways to take the bodhisattva vows and both are acceptable. The first way is not a kind of lie. There is no doubt in your mind that the altruistic mind of loving kindness is really your path; that bodhicitta is your deity, your Buddha, your Dharma, your Sangha, your bible—your Buddhist bible, your Hindu bible, your Muslim bible, your all world religions’ bible. This is the way you should think. When you take the vows you don't have to be nervous about breaking them because you have said, "I'll do as much as I possibly can," and you have not promised something that you can't do. You shouldn't feel that by taking the vows this way you are somehow cheating.

Many people have a commitment from certain initiations to practice the six-session guru yoga each day, in which they renew or make their bodhisattva vows clean-clear. Those who don't have this particular practice can still do the same thing. Six times a day, for just a minute, you can simply remember your commitment to the development of bodhicitta. You don't have to do anything dramatic, like Muslims bowing to Mecca. Wherever you are—standing or sitting or when you go to bed—just remember bodhicitta. That's good enough. Actually, there is a traditional way of doing this six times a day, with a visualization of the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions in front of you and a prayer to be recited, but there is no necessary requirement to do this. If you want to do this, it's good for reminding yourself about bodhicitta, but the other way is easier when you're amongst ordinary people.

When you get up in the morning, sit on your bed for a minute or two and think, "Today I shall actualize bodhicitta and make my life meaningful for others." That's all. Then take a shower, have breakfast and go off to work. You get a lunchbreak, so after you've finished your sandwiches and coffee, just sit for a minute or two and renew your motivation. The same thing before you go to bed. So, according to your daily life, you can find six times to do this short practice. It is simple isn't it, and it doesn't conflict with your culture. It's no big deal. But formal meditation, sitting cross-legged, is a big deal, isn't it? You cannot just drop into the full lotus wherever you are. And you can't mix sleep with formal meditation, but you can mix bodhicitta with ordinary sleep.

Thus, bodhicitta is the most worthwhile path. No argument, no worry about this. It is completely the right thing, something we can practice for the rest of your life. Really the best. Forget about tantra. Of course, if your tantric practice helps you grow bodhicitta, do it, but if you don't forget your bodhicitta from now until the time you die, you are totally guaranteed freedom from a bad rebirth. I can promise you that you'll not be reborn in an African desert! The mind that has bodhicitta is incredibly rich, an unbelievably rich mind. There is no way a person with bodhicitta has to go without water—a rich mind makes us rich. That's why I say the bodhisattva path is the most comfortable path to enlightenment. It’s very comfortable and very scientific. You don't have to worry that you're not understanding it or whether it's working or not. It's clean-clear; it's perfect.

For us it can be difficult when someone asks us for even a cup of tea. If the situation is right, it's OK, but when we are busy or something and someone says, "I'm thirsty, can I have some tea?" we get uptight, uncomfortable and unhappy.

When we have bodhicitta and someone asks us for a drink, no matter what we are doing we are delighted to be useful, to have a chance to help someone. In the old days, bodhisattvas used to be so happy when a beggar came to their door asking for money or something. They would think "He's so kind, helping me along the graduated path to enlightenment, helping me eliminate my self-cherishing," and they would give with respect. This is a good example for us. We live among people who are always demanding our attention, our time and our energy. Young people's parents, for example, ask, "Why don't you come home tonight?" or "Why don't you stay with us for Christmas?"

There is so much happening in our life; everybody wants something from us. It's true, isn't it? Definitely. Maybe good things, maybe bad things; our wealth, our body, our speech, our mind. It's complicated. Also, sometimes we are obliged to give our time or our body, even though inside we don't want to, so we give with an unhappy mind. But when we have bodhicitta and someone asks us to give our body, we do so happily. This is true; at a certain point it's true. This is a scientific situation; I'm not just joking. Sometimes we are obliged to give our body or our speech, so it is much better to give with happiness than with anger. It is no good at all to give anything with anger. When we have bodhicitta, where giving once used to cause us pain, now it makes us blissful. This is scientifically true.

Remember the story of one of the previous lives of Shakyamuni Buddha? It happened in Nepal: he was a prince, and one day went into the jungle to the place that is now called Namo Buddha. He saw a tigress who was dying and too weak to feed her cubs, so he took off his clothes and offered his body to the tigress. She was too weak even to notice him, so he broke off a branch of a tree, cut himself and let the blood flow into her mouth. Thus, she gradually regained her strength until she finally ate the prince. Then the king and the queen came along, saying, "What has happened to our gorgeous son?" Well, the gorgeous son had gone into the tiger's mouth, but he felt no pain because he had offered his body with great compassion. And this also caused his mind to develop much further along the path to enlightenment.

Similarly, Chandrakirti explained how a first level bodhisattva can offer his flesh to others, piece by piece, without pain. Each time he cuts off a piece all he feels is bliss. Such happiness comes from the power of the mind; it's not something physical. It is the result of bodhicitta, loving kindness. Of course, although these are good examples of the power of bodhicitta, we should forget about trying to make these kinds of offering. Neither can we nor should we think of cutting our body like this—we'd cry; we'd die. We have to be careful when we hear this sort of teaching. It is always emphasized that bodhisattvas should engage in such practices only when they are ready to do so. Until the mind is ready we shouldn't give anything like that.

Bodhisattvas even have a vow against giving certain things that they need for their practice—certain texts, for example. When we're in trouble we need to have our Dharma book to refer to, so we should never give it away; it is a reflection of the information a bodhisattva needs to follow the graduated path to method and wisdom. It is wrong to think that a bodhisattva should give everything. There are rules for giving: at this level we give so much, at the next so much, and so on. There are complete explanations, so don't make mistakes. A bodhisattva should follow the middle path and avoid extremes.

Now, the reason I’m telling you all this is that we are living amongst the problems of human life and we have to deal with them. That means that sometimes we do have to give a little of our time and energy, everything, to others. If we can give with bodhicitta our ability to give develops gradually and makes us blissful instead of tight and uncomfortable. Wrong giving is not worthwhile; I want you to have right understanding. Until you are on the first bodhisattva level you should never give your body: you are not ready for that. Don't give your eyes; don't give your heart!

So far I have met three students who have offered me their heart: "Lama, I want to give you my heart; please take my heart." I said, "Yes, whenever I'm ready I'll write to you." What else can I say? I was a bit shocked. I mean, I talk about bodhicitta, "Blah, blah, blah," and actually my students are really true bodhisattvas, saying, "Please take my heart." They make me lose my concepts! It's true—I have met three students who made this offer. They are very good, they mean well. I couldn’t give my heart! Anyway, who'd want it? It's a broken one with three holes and doesn't work properly.

The reason I have explained all this is for you to see that through the power of bodhicitta, loving kindness, even things that are very difficult to give can be given easily and with great happiness. That's a function of bodhicitta.

The bodhisattva's mind is very broad. When we adopt a religion, sometimes we become very dangerous, fanatical, closed. "I'm a Buddhist; I hate Muslims." This is very, very bad. With bodhicitta, we are completely open. The bodhisattva has space for all religions—Hinduism, Christianity, Islam. That's one of the most beautiful things about it. In fact, one of the bodhisattva vows is that we must never put down any other religion or a religion's philosophy. It even says that we should not put down the lower levels of Buddhist philosophy like the Hinayana. What other religion says that you shouldn't put down other religions or other divisions of your own religion? That's why we say that Buddhism has universal understanding of the entire universal human consciousness. We should understand that the bodhisattva path is completely open, embracing all mother sentient beings, all humanity, everything. There is no sectarianism, no discrimination against any other religion. This is the most beautiful thing to make us grow happy and healthy. I think it is wonderful.

Without this attitude, life on Earth is terrible. Some people accept one religious group but hate all others. They criticize and put down other people. This is the most dangerous thing, the worst example they can set. Observing this sort of behavior, non-religious people have no hope: "Look at how the followers of that religion act. They fight amongst and kill themselves and others. Who needs religion? It only makes more problems." I agree with people who say this; I can't blame them for feeling that way. Who wants to be like those religious fanatics? Inside they are most painful, most dangerous, and they damage others. It's so unhealthy. But if we follow the bodhisattva path, we embrace, we have space in our heart for all universal living beings.

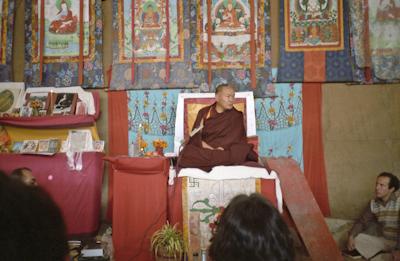

Now, as you take the ordination in one of the two ways, think as follows: visualize before you the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions of the universe. What are buddhas and bodhisattvas? Those who have attained high realizations in their consciousness, who have actualized bodhicitta, who have crossed the ocean of confusion and dissatisfaction in order to be of the highest benefit to limitless sentient beings. Consider them in this way and think:

"Today I am so fortunate. I have come to the conclusion that I must change my attitude of self-cherishing into that of holding others dearer than myself. I want to serve others, therefore my entire meditation and my practice of charity, morality, patience, effort, concentration and wisdom will be for the benefit of others, for me to grow better and better in order to serve them as best I can. This is my attitude today, my strong determination. I am so lucky, so fortunate to feel like this. It is the most precious thing in my life. This attitude is far more valuable than any material possession. I am so lucky to have it. And I am especially lucky to have discovered the real antidote to my unhappiness, my life of self-pity. There is no question that the solution is to follow the bodhisattva's path, to actualize bodhicitta. Without doubt, this is the most comfortable path. From now on, may I never separate from this wish, this determination, this pure enlightened thought. I shall actualize this thought and hold it in my heart twenty-four hours a day, as much as I possibly can.

"In front of the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions of the universe, in front of my lama, I make this request. Please give me the inspiration and strength to increase this determination continuously for the rest of my life, to make my life meaningful for the benefit of others. For countless lives I have held fanatical concepts, the selfish attitude concerned for ‘me, me, me’ alone, continuously reinforcing the cause of all misery and sickness. All suffering comes from this kind of mind, but now I have changed this thought into openness for others. I have created space in my heart for all universal living beings. I shall never forget this new experience and actualize it every day to the best of my ability.

"Buddhas and bodhisattva of the ten directions, please listen and pay attention to me: just as you have all actualized bodhicitta and gained happiness, today I too dedicate myself to the bodhisattva path. I shall actualize bodhicitta as much as I can and make the rest of my life meaningful and happy, truly happy and truly satisfied."

With this kind of motivation, take the bodhisattva ordination.