April 23, 2003

Causative Phenomena are Transitory

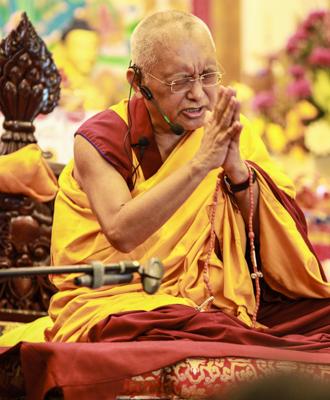

[Rinpoche chants Praise to Shakyamuni Buddha in Tibetan]

Do not commit any unwholesome actions, which harm oneself and other sentient beings.

Engage in perfect wholesome actions, which benefit others and oneself.

Subdue one’s own mind.

This is the teaching of the Buddha.

— Verse. 183, Dhammapada

Now we will meditate on these verses, as I explained yesterday, looking at causative phenomena—our own life, including our body and possessions that we have; the people surrounding us, including our family members, friends and so forth; and the sense objects, form, sound, smell, taste, tangible objects, all these enjoyments—as having the nature of impermanence like a shooting star, a shimmering [mirage], a hallucination, rab rib [defective view.] How they appear is not true. These phenomena are in the nature of impermanence, like a flickering light, and can be stopped at any time due to cause and conditions.

They are like an illusion, therefore how they appear is not true. They don’t exist in the way that they appear to our hallucinated mind. The possessions, all these enjoyments and the people surrounding us, as well as our own life, our own body, these things, including our own aggregates, even the I itself, all these are like an illusion. They are empty of existing from their own side. What appears to exist from its own side is like an illusion.

These causative phenomena are transitory. Their nature is transitory, changing and decaying not only minute-by-minute, second-by-second, but even within every second things are changing and decaying; they do not last. Like a dew drop they have a transitory nature and can be stopped at any time. They can be ceased at any time, like a water bubble that can be stopped any time. Their nature is transitory.

Things that appear are like a dream. When we see things in a dream, they appear to our mind even in the dream as real and we believe they are real, but that’s not true. After we wake up we discover they were totally nonexistent. All these causative phenomena are exactly the same. They appear to exist from their own side and we also believe that from our own side. In our own mind we believe that it’s true, but in reality there’s no such thing; all these phenomena are totally empty, like a dream.

Causative phenomena can be understood as transitory like last night’s dream, which happened but then it’s gone. Phenomena are transitory in nature. They appear then they are gone, like lightning. During a lightning strike, things appear but then the next minute they stop, so they have a transitory nature that we cannot trust. We cannot generate a belief of permanence—that they are always going to be like this, that we will always have this human body or these possessions or the people surrounding us, that we will have these things all the time and they will be like this forever. That’s not true.

Having all these things is just for a very short time, like lightning. We have all these things, then in the next minute they’re gone! The appearance of this life stopped. It happened and it stopped. Having this precious human body and all these things, having met the virtuous friend or hearing teachings, all these things that appear, the appearances of this life, they appear then they are gone, finished, like lightning.

All these are transitory in nature, like clouds in the sky. They are there but in the next minute they are not there, or while you are looking at them they are changing. They do not last.

Therefore, there is no reason at all to get angry, whether it’s toward a living being or a non-living thing. There is no point at all in getting angry; it is just total nonsense. Also, there’s no point in getting attached, whether to a living being or a non-living thing. There’s no point at all, because these causative phenomena have this transitory nature. The way these things appear is not true. Therefore, being angry or attached to something is another hallucination; it’s a double hallucination. It’s another superstition, another hallucination, therefore it doesn’t make any sense. It’s just total nonsense to be attached to these causative phenomena, which are transitory in nature. The way they appear to us is not true. They are totally empty of existing from their own side or being real ones appearing from there.

There’s no basis for getting angry or for the discriminating thoughts of anger, attachment or all the other delusions, including ignorance itself, to arise. There’s no basis for that. It’s just total nonsense, because things are empty of existing from their own side. We follow ignorance or we believe the projection that is put on merely labeled phenomena by ignorance. We believe that is true; we believe the view of ignorance is true. The projection, the view of ignorance, is a hallucination, but we let our mind believe it is true, rather than following wisdom and understanding the ultimate nature of phenomena, by looking at them as empty, as they’re empty, by looking at them in their ultimate nature. Therefore, even ignorance itself—holding on to phenomena as existing from their own side—is totally nonsense and has no meaning.

Motivation for Listening to or Teaching Dharma

[Rinpoche recites final verse in Tibetan]

Our activity here, listening to the teachings or explaining the teachings, doesn’t necessarily become the cause of happiness. Just because it looks like spiritual action, that doesn’t actually make it a spiritual action or Dharma. It may look like Dharma action, but that alone doesn’t necessarily make the action actually become Dharma.

If listening to the teachings or explaining the teachings is done out of anger or even with worldly concern or attachment clinging to this life, then that motivation is nonvirtue. So then the action of listening to teachings or giving teachings becomes nonvirtue and the result is only suffering.

If listening to the teachings or giving teachings is done with attachment seeking samsaric happiness—even if the motivation is for future life happiness—then it doesn’t become the cause of achieving liberation from samsara. It just becomes the cause of samsara.

If listening to teachings or giving teachings is done with ignorance, the concept of true existence, then it doesn’t become the antidote to samsara and its cause, the delusions. It doesn’t become the antidote to the particular root of samsara, the unknowing mind.

This cognition or knowing phenomena functions in a totally opposite way to wisdom, which functions by apprehending that the object is empty, as it is empty. That unknowing mind does not know that the I which appears to exist from its own side is a hallucination and is nonexistent; it does not know the ultimate nature of the I. If explaining or giving teachings is done with that ignorance which apprehends that things exist from their own side, then it does not become the antidote to that, therefore we need to seal it with emptiness.

The I which exists is merely labeled by mind; the action which exists—giving teachings or listening to teachings—is merely labeled by the mind; and the object—the one to whom we give teachings—is merely labeled by the mind. Therefore all three are empty. The I is empty, the action is empty and the object is empty, so seal these with emptiness.

Similarly, when we make charity, the perfect way to make charity is by sealing with emptiness by looking at the three circles—the subject, I, the one who makes charity; the action of making charity; and the object to whom we make charity, and also the materials. All these things are merely labeled by mind, therefore none of these things exist from their own side. They are empty. This is explained in the teachings of the six paramitas, when we make charity by sealing the three circles with emptiness.

Even when we do a fire puja, the burning offering practice, offering to the deity, one of the main instructions is doing the offerings and sealing with emptiness.

All these things appear as truly existent but we look at these three things as like a dream, like an illusion. By looking in that way then the resultant understanding that comes to our heart is that oneself, the action of offering, the offerings and the deity to whom we make offerings are all empty. Thus, it becomes a pure offering unstained by ignorance; our charity becomes pure, unstained by ignorance.

It’s the same here. If we are able to remember to seal with emptiness then also here when we listen to or give teachings it also becomes pure, unstained by ignorance. In the thought transformation text, it says, “Give up the poisonous food.” Even when we practice Dharma and do these things, if it’s done with ignorance it is like poisonous food. It’s poisoned by ignorance, believing all these things are inherently existent, and it doesn’t become the antidote to samsara. The ignorance itself doesn’t become a remedy or an antidote to the root of samsara, ignorance. By looking at this and by sealing with the emptiness, then it becomes the antidote, the remedy to samsara and the root of samsara, ignorance.

It is true that teaching Dharma benefits the mind of the person who is teaching. Maybe that’s part of the benefit, I think—benefiting the person who is teaching, benefiting their own mind. I think here, because I’m talking, it reminded me about my practice.

If listening to teachings and giving teachings is done with the self-cherishing thought, then it doesn’t become the cause to achieve enlightenment. If listening to teachings and giving teachings is done with renunciation of this life, the first Dharma, the very beginning Dharma practice, the detachment from this life, then the action becomes the cause of happiness of future lives. If listening to and giving teachings is done with renunciation of samsara—the whole entire samsara, including the future life’s samsara—then the action of listening to or giving teachings becomes the cause of achieving liberation from samsara.

If it’s done by sealing with emptiness, then it becomes a remedy to samsara and the root of samsara, ignorance. Instead of developing ignorance, the root of samsara, then this becomes the antidote to destroy that, to eradicate that.

If it’s done with a bodhicitta motivation, then listening to the teachings and giving teachings becomes the cause of achieving enlightenment.

By achieving that [bodhicitta] it enables us to do perfect work for all the sentient beings, to be able to free the numberless sentient beings who want happiness and do not want suffering. We are able to free them from all the suffering and its causes and bring them to peerless happiness, full enlightenment.

How to Benefit Others

Here, think, “Therefore the purpose of my life is to benefit others, to become useful for other sentient beings.” There are different levels of benefiting other sentient beings. The first level is by bringing them happiness of this life. One way of benefiting others is by doing consultations and solving their emotional problems, relationship problems, depression or whatever problems that they have. By solving those problems they will have peace and happiness. We can also benefit sick people by giving them medicine; we can help those who live in poverty without food or drink, by giving them food and drink; we can help those who don’t have shelter by giving them shelter, and so forth. We can do all these things, giving them either mental comfort or physical comfort and thus causing happiness of this life.

A more important benefit for other sentient beings is offering them the happiness of future lives—not the happiness of just one future life but the happiness of all the coming future lives. We can create the cause for numberless sentient beings to have happiness in all the coming future lives. That is a much more important service than the first way of benefiting others.

The third service to other sentient beings is bringing them to everlasting happiness by ceasing all their suffering and its cause, delusion and karma. This way of serving others, by ending their samsaric suffering which is continuous and has no beginning, is much more important. We’re creating the cause for other sentient beings’ suffering of samsara to end, by ceasing delusion and karma. So this becomes a much more important service and much more urgent than the previous ones. Bringing them this everlasting happiness is an emergency service for sentient beings.

Even more important than that is bringing sentient beings to the peerless happiness, full enlightenment—the cessation of not only the gross mistakes of the mind, the defilements, but even the subtle mistakes of the mind, thus ceasing all the mistakes of the mind and having all the qualities of the mind. Bringing sentient beings to full enlightenment, to that peerless happiness, is the most important service and that is the greatest benefit that we can offer to other sentient beings.

This is how to bring happiness to other sentient beings according to different levels of benefiting them. In this way, we can make our own life useful and beneficial for others.

Now, by achieving enlightenment we are able to do perfect work for sentient beings without the slightest mistake. We can bring them from happiness to happiness to full enlightenment, having perfect understanding, the omniscient mind, and having perfect power to reveal any method that fits with them according to their karma, their level of intelligence and their characteristics of mind.

Also having perfect compassion, with the mind that has completed training in compassion and has nothing more to develop toward each and every sentient being. There is no more compassion to develop; we have completed mind training in compassion, so it’s perfect compassion. This compassion does not cheat sentient beings and if they rely on us we don’t give up, we don’t cheat them, we don’t give up sentient beings. Whether sentient beings make offerings to us or not, whether sentient beings criticize us or whether they praise us, there is compassion. When we become a buddha we have a hundred thousand or a million times more compassion for sentient beings than what they have for themselves—how much they love themselves or cherish themselves.

When we become a buddha the love and compassion that we have for sentient beings, how much we cherish them is much more—a hundred thousand or a million times more—than how much sentient beings cherish themselves. Because of this compassion, it does not allow us to cheat sentient beings or to not give guidance to them. It doesn’t allow us to not give guidance and because of the compassion we guide all sentient beings without any discrimination and we do perfect work for all the sentient beings.

Therefore think, “The purpose of my life is to free numberless sentient beings from all the suffering and its causes and bring them to enlightenment. Therefore, I must achieve enlightenment; therefore, I’m going to listen to the teachings.”

Every time we listen to the teachings, at the beginning generate bodhicitta at least like that. Listening to the teachings is for all sentient beings, so feel that they are in our heart, just as we feel a friend that we cherish so much is in our heart, or we feel that our mother or father or somebody who is very kind to us is in our heart. Like that, feel that all sentient beings are in our heart and we are listening to the teachings for them.

We should have this attitude not only when we listen to teachings and not only when we do sadhanas or sessions during retreat. We should practice like this twenty-four hours a day—having this attitude, this feeling, having sentient beings in the heart and doing our activities for them. We should have sentient beings in our heart and do things for them. We go to sleep for that purpose, we eat and drink for that purpose, we study Dharma for that purpose, we go to work for that purpose, we do our washing to benefit them and so forth. Whatever activity we do, we do it for sentient beings, just as a mother who has one beloved child, whatever activities she does, she always has that child in her heart all the time, twenty-four hours a day, then she buys things or does many things for that child. By having the child in her heart she does so many things for that child.

In our daily life we should have that attitude for whatever activity we do. We shouldn’t only have the motivation of bodhicitta in the beginning, at that time feeling we are doing the action for others; at first thinking we are doing the work or the action for sentient beings, but there’s no continuation. In the beginning for a few seconds or a minute we motivate like that, but then nothing, then it becomes work for ourselves the rest of the time. The motivation did not last; we had the thought to benefit others at the beginning but then it didn’t last, then it became work for ourselves the rest of the time, whether it was a sadhana or doing some social work or whatever work for others.

Therefore, we need to watch our motivation again and again throughout our activities. We need to watch our motivation. We need to generate the motivation of time; not only the motivation of cause before the action, we need to generate the motivation of time, the thought of benefiting others throughout the action. If we watch the motivation from time to time and it becomes work for ourselves then we should change it immediately to working for others. While we are doing a sadhana or doing social service or listening to teachings, studying Dharma or reading Dharma texts, whatever, or doing our job, as much as possible try to keep the motivation. As much as possible put effort into the work we do so it becomes for others. As much as possible we should watch our motivation, our own attitude during the action, watch it again and again, and if it becomes work for self then change the attitude again to the thought of benefiting others.

In daily life, practice like this. Also actually engage in the practice of lamrim on the basis of guru devotion, which is the root of the path to enlightenment. This makes all the practice and all the realizations successful from perfect human rebirth, the beginning of the path of lamrim, up to the enlightenment. What makes everything successful is to actualize [bodhicitta] in order to liberate the numberless sentient beings from the oceans of samsaric sufferings and bring them to enlightenment. So in daily life, put effort like this. Of course if you have a stable realization of bodhicitta, then of course you don’t need to put effort. Naturally, there’s no other motivation once you have the realization of bodhicitta. There’s no other motivation except cherishing others and only thinking of seeking happiness for others. Then whatever you do, everything is naturally for others.

Gen Jampa Wangdu’s Realization of Bodhicitta

It’s like Gen Jampa Wangdu, who was one of the oldest meditators among those who came from Tibet and meditated in Dharamsala and Dalhousie, which is close to Dharamsala. Among those earlier meditators, he was one who had the greatest success in having realizations and from whom I have taken the teaching on the pill retreat, taking the essence. If you are living in a very isolated place where it is very difficult to get food and it takes many hours to bring food, you can live on the pills. Also you have less activity so you have more time to meditate and a very clear mind. With that very clear mind I guess it’s easier to achieve shamatha, the perfect meditation, calm abiding, the basis of great insight and the basis of the arya path, the basis of liberation.

Before Gen Jampa Wangdu passed away—this was right after Lama passed away in the United States—he made a comment, as he told us his story, that it had been seven years since he went to other people’s houses for his own purpose. He said, “I have never been to anybody’s house for seven years just for myself, for my own purpose.” That doesn’t mean that he didn’t go to other people’s houses for seven years. What it contains, what it implies or means is that he generated bodhicitta seven years ago. I think that day when we met him, it means that he had the realization of bodhicitta seven years ago. So when he went to other people’s houses there was no thought of seeking happiness for himself. It didn’t arise even for one second.

Once you have stable realization of bodhicitta, while you have realization of bodhicitta you have no thought of seeking happiness for yourself. It doesn’t arise even for one second. There is only the thought of seeking happiness for others and you are only working for other sentient beings. I don’t remember the context, the conversation, but it means that whatever he did in the past seven years, even breathing in and out, everything was for other sentient beings.

He has some older students, lay and Sangha, those who were there during the first Dharma Celebration. Almost all of the Sangha who were there received the pill retreat teaching from him. Maybe I mentioned, I’m not sure, that Lama made the request and Lama was the translator. Geshe-la gave the teaching and Lama translated, something like that. I was not there at that time. I took the teaching much later, before he passed away, in case that teaching became kind of rare in the future.

So in daily life you should put effort into an attitude like this and then on the basis of guru devotion, develop that. Then train the mind in the actual body of the practice, the actual body of spiritual development, the lamrim, developing the mind in the path step-by-step. First have renunciation of this life, then renunciation of next lives, then bodhicitta. You can’t have realization of bodhicitta before that; you can only achieve realization of bodhicitta step-by-step, like that. You have to direct your own life; you have to set up or direct your own life in this way.

This is how to progress; this is the procedure for bodhicitta realization, which becomes the procedure for enlightenment. You have to do other things in our daily life but the main project in your heart, on the basis of developing guru devotion and correctly devoting [to the guru], is to develop the Mahayana path. You need renunciation of this life, making your own mind free from attachment clinging to this life. You become independent, free from the attachment clinging to this life and free from the attachment to future samsara. Then you develop bodhicitta.

At the same time, while you are doing that, you can also work on emptiness—to realize emptiness and develop that wisdom. Just to realize emptiness is not sufficient. You have to develop wisdom and achieve great insight. By developing that wisdom then you achieve great insight; you achieve the wisdom directly perceiving emptiness, the arya path. You should continue like that so that you can directly cease the gross defilements and also the subtle ones with bodhicitta.

Along with this, you need to practice purification and collect merit. You should practice purification, pacifying the obstacles, the negative karma and the defilements, and creating the necessary conditions by collecting extensive merit. Not only doing those traditional particular practices of purification or collecting merit, but of course you should do those as much as you can. The most important thing in our life, as so many of us have many obligations or engagements—maybe there’s time to do those particular practices of purification and collecting merit, those preliminary practices, but if we are unable to give a lot of time to those practices or at the moment life has become difficult to do much—I think the very important thing in our daily life is that whatever we do, we should try to make everything become purification and the means for collecting extensive merit by understanding lamrim.

Whatever activity we do—working, eating, walking, sitting, sleeping, the normal daily things, whatever activity that we do—transform that or make that itself a great purification for our own mind, to purify the defilements and negative karma. Make that itself the means to collect extensive merit.

Therefore, even if you don’t have time to do those particular traditional practices of purification, the preliminary practices, even if there’s no time, try to make whatever you’re doing a powerful preliminary practice; a powerful practice of purification and to collect extensive merit. With the skillful means knowing how to practice Dharma, knowing those essential techniques, this is what makes our actions the most powerful purification. This is what makes these normal actions that we do in our daily life collect the most extensive merit. In this way, as a minimum it also helps our daily life activities, whatever we do, not become negative karma, the cause of suffering. That’s the very last thing, so it also helps that.

Is there some example of an activity that we do normally, to make it collect the most extensive merit and become a most powerful purification? Something that we do normally?

Student: Sleeping.

Rinpoche: Sleeping? That’s also my problem. [Laughter] We have the same problem.

No, I was going to explain those things one day, but anyway, I think even if you know the various techniques, if you are practicing tantra, there’s sleeping with creativity and non-creativity, the state of non-creativity or creativity and also rising up. I think even if you know the techniques that doesn’t mean that you are able to practice.

Lama Yeshe’s Clear Light Meditation While Showing the Aspect of Sleeping

I think you have to plan far ahead of the time that you are going to sleep in this way. For the practice of sleeping, think, “With this technique, I’m going to sleep.” So you make a strong decision or a plan. I think if that is not done then it will never happen. For example, if you are going to a party then you need to make a strong plan, “Oh, tonight I’m going to go to the party and I’m going to dance,” or “I’m going to dinner at somebody’s house.” You have a strong plan. So like that you have to plan, then it can happen.

Then in this way, as you do it more and more, it can be a regular practice and sleeping becomes a virtue. It’s dependent on the level of the practitioner. For those who are practitioners of tantra and who are able to recognize clear light, then however many hours they are sleeping, it’s all like an atomic bomb. They are meditating on the clear light, which destroys the dualistic view, the defilements, like an atomic bomb. That is the realization which is the cause of achieving enlightenment in a brief lifetime of degenerated time.

In lower tantra we can achieve enlightenment in one life, but that means first achieving immortal life. First by doing long-life meditation we will achieve immortal life so that we can live for a thousand years and then we achieve enlightenment, but here [in Highest Yoga Tantra] we achieve enlightenment within a few years. Here, achieving enlightenment in a brief lifetime of degenerated time means in a few years. The cause for achieving that is actualizing the clear light, as Lama Yeshe did.

Therefore, the entire sleep is meditation. Lama asked people who were upstairs at Kopan to not make noise around him. He wasn’t like many people in the West who cherish their sleep so much, like a jewel. They cherish their sleep so much and therefore they say, “Do not disturb.” It wasn’t like that. It wasn’t that way. It was a very important meditation; it was not just meditation on the three principal aspects of the path, it wasn’t just that. It was the Highest Yoga Tantra meditation on the clear light. The very important thing, as I mentioned, is that by having that realization we achieve enlightenment. The yogi who has that realization has the possibility of achieving enlightenment in this life, in the same body, in a brief lifetime of degenerated time, so of course that meditation becomes unbelievably important, there’s no question.

So Lama was asking people, us, to not make noise around him at nighttime and during the day after a meal, when Lama took one and a half hour’s rest. He laid down—he didn’t sit up, he laid down—which normally was shown as taking a rest because of his heart, but actually it was a meditation session. He did not show that, “Oh, I’m doing a lot of practice,” or something like that. He laid down and in that way he did a meditation session. If Lama missed that then he felt a great loss. It was not just ordinary sleep.

One time at Kopan, Lama’s best friend, Jampa Trinley, who was in the same class as Lama in Tibet [came to visit.] One of their teachers was Geshe Ngawang Gendun, who was a very famous teacher in Tibet. At Sera, Ganden and Drepung, among so many thousands and thousands of learned ones he was maybe not the very first but the second most famous teacher. He was Geshe Sopa Rinpoche’s teacher and Lama’s teacher. So he passed away and reincarnated [as Yangsi Rinpoche, the child of] Lama’s friend, Jampa Trinley, who was a monk in the same class as Lama in Tibet. Later Jampa Trinley changed his life and became Nepalese; he got married and came to Nepal. He and his wife were the parents of Yangsi Rinpoche and Tsen-la, the nun who has been translating for a long time. Their father, Jampa Trinley, was in the same class as Lama and he was a very close friend.

One day Lama’s friend, Jampa Trinley, came to Kopan and Lama didn’t get his usual one and a half hours’ rest. Afterwards Lama acted as if he had lost a jewel. He wasn’t just missing the sleep; it was the continuity of his experience, what makes the clear light realization. It takes three countless great eons to achieve enlightenment in Paramitayana sutra—you need to collect merit for three countless great eons to achieve enlightenment—but here you finish all that merit within a few years by having the realization of the clear light and illusory body. As I mentioned before, that’s most powerful for those who have that realization.

Anyway, we need the motivation of bodhicitta. We have to take refuge in that, we have to rely upon bodhicitta. We have to take refuge in bodhicitta to make sleeping most beneficial. We have to rely upon bodhicitta, having the motivation of bodhicitta, dedicating for sentient beings as medicine or as food, for their health and also to affect their mind, for both. That is practicing Dharma for sentient beings, being able to offer service to sentient beings. Here, by relying upon bodhicitta for our motivation, then we can make that the means to collect the most extensive merit because it’s done for the benefit of numberless sentient beings. Therefore we get numberless merits.

It’s 9:30 or 10:30? [Inaudible comment from a student] Only? [Group laughs]

The Label Z is Imputed by the Mind

So, everything came from the mind. This is one explanation or one analysis, as I explained this afternoon. I suggested doing a walking meditation along with practicing awareness of that.

This afternoon I mentioned that, using the letter Z as an example. Before we were taught by somebody that “This is the letter Z”—going back to our childhood time, before we were introduced by our teacher or the person who writes on the blackboard or on paper with this design [Rinpoche draws in the air]—we saw the line or the design but we didn’t see that this was the letter Z until we were introduced to the label Z by somebody. We just saw the design, which is the base to be labeled Z. We just saw the design, which is the base. At that time, we didn’t see that this is Z because we didn’t have the appearance that this is Z. Our mind hadn’t labeled that this is Z and believed that, because we were not yet introduced to the label Z by somebody else.

Only later, somebody introduced us to the label by pointing to this design and then saying, “This is Z.” Somebody introduced the label Z to us, then we believe in that and our mind also labels Z. Our mind simply thinks that; our mind merely imputes Z and believes in that. It’s not something concrete put there. Our mind just simply thinks “Z” because somebody told us it is Z and we believe in that. Then after that, there’s the appearance of Z. After that, we see Z.

There’s all this evolution that comes from the mind until we see “This is Z.” So the appearance of Z comes from the mind; it is projected by the mind. The appearance came from the mind, so the Z that we see came from the mind. The Z that we see came from the mind; it is created by the mind.

It’s like that for “I.” The I which is appearing to us came from the mind in exactly the same way. The I that we see came from the mind. The I that we believe—whether it’s merely labeled, whether it’s truly existent—is projected by our own ignorance, our own mind. It all came from mind. Whether it’s hallucinated, whether it’s a false I or whether it’s the I that exists, it is merely imputed by the mind; it all came from the mind.

In the same way, the aggregates—for example, the whole body, which is a collection of limbs and body parts—also came from the mind. The merely imputed one, the truly existent one, the false one, all came from the mind. Going down to the atoms of the body and the particles of the atoms, all that, it is a merely labeled body. We think the body truly exists and has inherently existent atoms, but it’s a projection of the mind. So everything came from the mind, totally.

And then the different thoughts according to their function are labeled this and that—this is desire, this is anger, this is loving kindness, this is compassion. There are different mental factors, and the five that are called the omnipresent mental factors arise at the same time as the [principal] consciousness and have different functions, relating to the same object. There is the same object of consciousness and those different mental factors exist, just as a king has ministers or an entourage around him. Like that, the consciousness [apprehends an object] and those five mental factors accompany it, each having a different function. Because of that, each thought is labeled this and that. Each thought has a different function. There is the base and then different labels are put on that base, this and that.

Contact, feeling, intention, comprehension—different labels are imputed or made up depending on those different thoughts that have different functions relating to the same object. Anyway, all six consciousnesses and fifty-one mental factors are merely imputed. All those different labels which are made up—that are thought or imputed—came from the mind. So everything is labeled or imputed by the mind, according to the base and the different functions that they have.

All phenomena—sounds, smells, tastes, tangible objects, the whole of phenomena—came from the mind. Just as the appearance of Z came from the mind, the rest of the phenomena—this and that, all that we see, each of the senses—all came from the mind. We don’t see those phenomena without them appearing and we don’t have the appearance of those phenomena if our mind has not labeled this and that.

It’s the same for friends—friends came from the mind and enemies came from the mind in the same way. Enemies came from the mind; our own mind just made it all up. There is nothing there. Our own mind just made it up through the concepts, so like that.

Stories of Rinpoche’s Early Childhood

When I was in Solu Khumbu—not at the other place [Rolwaling] where I lived for seven years—I escaped a few times from the monastery where my first teacher, my uncle, was teaching me the alphabet. I ran away to my home because it was quite close. From the monastery I could run down to my mother’s house in the village. Just the thought came to escape; just the thought came to run away. That was the main thing; there was no other important reason. There was no other emergency. I just thought, “At home I can play; I am free or I can play.” There was nothing profound; there was no profound commentary or something. Just that, very simple. So I thought that and then I ran away. The thought always came to go to home to play. The thought came and then I just did it, like that. [Laughter]

Anyway, I think I did that maybe two or three times, not many times. One time there was snow and I was blowing into one plant that had a very good sound, but not like a didgeridoo, not quite like that. Maybe somebody can play that, maybe it can happen, but anyway, I was playing that, somebody had given me that. So I was playing this and the thought came into my mind to run away. My teacher had gone inside to make food. I think we had food three or four times each day, something like that. So he went to make food and the thought came into my mind to run away.

My mother had given me my first clothing. It was a pair of pants joined together with another part [a shirt]. I think that was the first time I had worn pants since I was born, but they were made of the very cheapest cloth, which in Solu Khumbu was used for prayer flags. I think it is a little bit thick; the same quality but a little bit thick. It’s red, kind of pink or red. I had the pants [and shirt], and where the two were joined together there were a lot of lice around there. That was a good place for lice, where the two were joined together. That was usually a good place for lice. Anyway, I didn’t know how to remove the pants when I had to go to the toilet. I had no idea.

When I escaped, I ran from the monastery down to my mother’s home. There are many caves, big rocks and dark caves, and I was scared of those dark caves, so I used to run nonstop until I reached mother’s house. However, I didn’t know how to open the pants. So from the monastery I ran down to my mother’s house and somewhere along the way I went to the toilet in my pants. I was carrying some luggage in my pants, like carrying a bag or something. [Laughter]

When I reached my mother’s house, she was outside talking to some old people from around there. Then she took off all my clothes and cleaned everything in front of all the people.

Anyway, what was I saying? This is just side talk. Oh, yeah, that’s right. So because I escaped a few times my mother sent me to Rolwaling. This is also Padmasambhava’s hidden holy place and it’s much more primitive there than on this side of Solu Khumbu. I lived there for seven years but I did come back two or three times with my second uncle, who taught me the alphabet the second time, to see my teacher. So I came to this side of Solu Khumbu to receive teachings and an initiation from the lama from Thangme Monastery—the old lama who I have described—and also to see my mother. I came maybe three times, something like that.

I think the first time I came back with my uncle—I don’t remember, but it might be the first time I had returned after quite a number of years—we went to my mother’s home, where she offered us alcohol made of potato. It looks like drinking water, but it’s unbelievably strong alcohol.

My mother quite often made potato alcohol and for a few hours it took a lot of firewood. At my home, there was nobody apart from small children. Only my sister could do a little bit of work. She would go out and put the animals out on the mountain and bring them back in the evening time. That was all she could do. The rest of us were very small. All we did was just eat food that our mother gave us and play all day long, in the fields and at home, that’s all. There was no help for our mother, nothing. She had to go alone very far into the forest; it was very difficult. She went for many hours into the forest to collect firewood, then she had to bring a very heavy load back home. She came back at nighttime.

One night she didn’t come back; one night she took a long time, so I think four of us children sat waiting for our mother outside the door. The house had two stories and we sat outside the door, all lined up, waiting for our mother. The moon was rising and then after a long time she finally came with a huge load of firewood in a bamboo basket. Until then nobody knew how to make a fire; no one knew how to make a fire or cook food, so we didn’t eat food until our mother came.

I don’t remember seeing my father. I have no idea about my father. I think my father died maybe when I was in a small bamboo basket or in my mother’s womb, I’m not sure. But people described how my father looked and how his mentality was. They said he didn’t get upset or angry easily. He was—I don’t know the expression—tolerant, something like that. The only thing I remember is that the blanket that the whole family used to sleep in was my father’s chuba—my father’s dress with sleeves, made from animal skin with fur inside. It was an animal skin chuba with sleeves, so that covered the whole family. I remember being introduced to my father’s chuba and holding it.

One time my mother was sick. I’m not sure, maybe it was a headache, or I don’t know what. At home there was a square fireplace, a stove, and usually there was a fixed place to sit. My mother would sit there and usually I’d sit here, then my brother—the younger brother, the one who’s married and lives near Boudha Stupa—and then my sister. So here’s the wall and usually there was a kind of fixed place to sit around the fire. There was another sister besides Ngawang Samten, the one who lives at Lawudo and became a nun. There was another one, but she died. The other sister who passed away had a short tail at the back, I think.

Anyway, my mother was very sick and I think maybe it was so painful that she was calling her mother, “Amala, Amala.” She was calling her mother. We children could not do anything. Everybody was too small. I just went to be with my mother, but nothing could be done. Usually our mother was the only one who made the fire and gave us food, everything, so that day there was no fire and no food. I don’t know how long that lasted, but anyway.

Actually the point is, when we arrived there one time, my mother gave us potato alcohol, the strong one. She offered a glass to my teacher and to myself. Normally I didn’t drink that; I drank the other chang made of rice—this is what my teacher made. In Solu Khumbu there are one or two monks who don’t drink, but drinking becomes a kind of tradition; not tradition but a habit. Anyway, at that time I wasn’t a monk, because I only became a monk in Tibet at Domo Geshe’s monastery. But the chang that we drank was not this strong one.

Anyway, I had a few sips of the potato wine that my mother gave me and after that my body had no control at all. [Rinpoche and group laugh] So my teacher, who was my uncle, just grabbed me by the backside and dragged me up the road. As he was walking up to the monastery he just dragged me like this. So my limbs were like—if you can remember how a mosquito looks when it is dead; when a mosquito or fly is dead, how the limbs are. So like this. [Rinpoche demonstrates] I couldn’t use my limbs, I had no control at all. There was no freedom at all over the limbs, so my teacher just held me here and dragged me to the monastery. I was extremely uncontrolled. After that I never had potato alcohol.

Since I’m telling you a story, I remember after I went to the other much more primitive place [Rolwaling]—I think maybe after one year or two years, I’m not sure—I wrote to my mother. I wrote by myself, but I had not studied writing; it was just my own writing. I think it was written with charcoal from the fire, not with a pen. We didn’t have a pen, just charcoal from the fire, which I used to write on the paper. I think in the message I was asking my mother to send a letter saying I should come back home.

I gave the letter to somebody who was traveling to Thangme, asking my mother to send a letter back to ask if I could come back home. So I gave the letter to somebody and what happened was, this person could not find the letter to give to my mother. He could not find the letter when he arrived there. After he came back, he was changing his shoes—the Sherpa shoes in which you put grass to keep your feet warm. Not socks, but like socks, with dry grass inside to keep the feet warm. You have to change the grass often, because if it becomes wet then it’s very cold so you have to change it, then each time you change it you feel so warm. It’s like wearing socks. So he was changing his shoes, he was cleaning his shoes and taking the grass out, but the letter I wrote had somehow gone inside his shoes, and it was only after he came back when he was cleaning his shoes that the letter came out.

So I did the same thing as Lama Ösel, who asked from Sera after two or three years, or one year there, I’m not sure. Lama Ösel wrote to Maria, his mother, saying “Please come to pick me up.”

Anyway, as a small child there’s not much deep thinking, you only want to play. You think only of play and comfort, and don’t have wide thinking of life.

So I came to take initiations and to see my mother, and then went back and stayed there for seven years. I had to read Dharma texts all day; it was a kind of training. Sometimes I thought my teacher, my uncle, had gone very far away. I was supposed to read the text and I turned many pages as if I had finished reading them. I thought my teacher had gone very far away, but actually he came back after some time and he could not hear that I was reading. Anyway, things like that happened. Of course, from my side I didn’t study; I did this kind of thing, being naughty. So it’s not that I followed every advice and was very obedient and humble.

Anyway, of course then I played. I’d still be there on the same seat, but I would just play with things, whipping with thread or watching the spiders. There were a lot of spiders making webs; they made the spider’s website. [Laughter] So I spent time teaching the spiders; I wasted a lot of time when my teacher was not there. I threw papers or small pieces of wood or something like that into the spider’s website, and then the spider didn’t know, the spider didn’t have clairvoyance, so he came there, but actually it was a piece of wood or a rolled piece of paper, so he couldn’t eat it and I think he dropped it. He couldn’t eat it so he dropped it.

There were a lot of tiny flies in the summertime flying around in space. I have these heavy karmas to be purified, because I hit those tiny flies flying in the sky in the summertime. I hit them like this [Rinpoche demonstrates hitting the fly between two hands] and then gave them to the spider. So there are many of these negative karmas to be purified.

One time when I was being naughty—I think it was in the summertime and there was a lot of water in the courtyard after it rained—my teacher took off all my clothes so I was naked, then he grabbed me and put my mouth into the rainwater on the ground. Or a common one was a dried bamboo stick—he would hit me on the head with a dried bamboo stick. Each time he hit my backside or head, the bamboo broke into pieces and sprang into the sky. That happened quite a few times.

Then one time, I don’t remember what I did, but my teacher took me outside the door, the gate of the house [to punish me.] There is the house like this and there’s a courtyard that has firewood piled up like this so it becomes a wall and then you can use the firewood from there. You collect wood for one season and then throughout the whole year you can use the wood from there, so it’s also a wall.

Outside the door of the house there were some nettles—a whole bunch of nettles was growing there. I don’t remember what I did, but my teacher took me outside and rubbed the nettles on my backside. Normally when you touch nettles like that you feel so much pain, but that time I didn’t feel much. I don’t why, but I didn’t feel much suffering. Normally, when you touch nettles it is very uncomfortable, but I don’t have the impression that I suffered much by having nettles rubbed on my backside.

Anyway, then my teacher let me read the Diamond Cutter Sutra over and over again, I don’t know for how many months. There’s another text, Condensed Sutra, that’s also very hard to read. Now, after many years, I see that my uncle beating me was all for my benefit, for me to become good. All the beatings, the scolding and letting me read these texts over and over, now I see definitely there is great benefit. The tiny bit of understanding of Dharma and being able to have faith in Lama Tsongkhapa’s teaching on emptiness—being able to have faith in Lama Tsongkhapa’s explanation of emptiness and then having some tiny bit of understanding—that came from those early times and the purification from my teacher beating me. When I made mistakes, he beat me and he let me read all these scriptures, so definitely how I can benefit now, even though it’s very small, very limited, it came from there. So that is the source, all the positive imprints and purification.

What I was going to bring up is this, but it just became long.

When I was in this very primitive place [Rolwaling] for seven years, it was the first time I saw a Westerner. The people were from France or I’m not sure where, but that was the very first time I had seen a Western person. I think that maybe two or three people came to my teacher’s house and that was the first time I saw Westerners. The impression, my feeling was that they were kind of very strange. My feeling was that they were very strange. Their hair was all yellow and they were very strange, I think maybe they also had hair here or something like that. Very strange. And the eyes, I think maybe they were blue, I’m not sure. Maybe they were from Germany, I’m not sure. The eyes and the language, I don’t know which country they were from. What I recollect of the language is piss, pisss, piss, pisss. [Laughter] Something like that, that’s the impression that I had the first time. I was watching them and thinking they were very strange.

Anyway, I was talking about how things came from the mind. So now, of course, my view is different, but at that time it was like that, very strange.

They gave us chocolate, these brown squares, and it was very funny, it had a very strange taste. I didn’t like it because it had a very strange taste. The Solu Khumbu people liked the bottles, the containers, the jars and things like that, but not the things inside, which were very sweet or something. Anyway, I had a different view and at that time I saw Westerners as totally strange.

In some countries many people have goiter. There are places, countries, where many people have goiter. In Solu Khumbu many people had that in past years but now they know that they can have an operation. In the past there were many people who had goiter, but recently hospitals were built and people now know that they can be operated on.

In a country where many people have goiter, it’s very common and it’s nothing strange. Then if somebody who doesn’t have goiter comes to that country where a lot of people have goiter, people think, “Oh, this is a very strange person,” because he doesn’t have goiter and the rest of the people have goiter. So here, good and bad came from the mind. Here, having goiter is good because everybody has it, then if someone who doesn’t have goiter comes, it’s very strange and they look at it bad.

Also, one lama explained in a commentary on Bodhicaryavatara that when something is not familiar to our mind, then we think it is strange or bad or something like that. This lama used the example of a monkey grabbing a human being, and the monkey thinks, “Oh, this human who doesn’t have a tail is very strange,” because monkeys all have tails. So when the monkey grabs a human being who doesn’t have a tail, that monkey thinks it is very strange. Instead of thinking not having tail looks good , they think it looks strange. Anyway, I thought that was quite interesting.

So good and bad, enemy and friend, all this come from the mind. Until we label "problem" in our life situation, we don’t have the appearance of a problem and we don’t see a problem. We have no appearance of a problem; we don’t see that this is a problem until we label it. After we label the problem in our life situation, then as we believe in our label, we have the appearance of a problem and we see that this is a problem. Again, here the life problem came from our own mind. The problem that we see, that we believe, came from our own mind.

Therefore, Naropa said that happiness or suffering are included in our superstition. Suffering or happiness are all included in our superstition. Naropa said, “When there’s harm, your superstition is harmed. When there are sicknesses, your superstition is sick. Even when death happens, superstition dies. Even when birth happens, superstition is born. So all superstition…” [Tibetan] I don’t remember the last part.

So, if we are able to cut the root of superstition, then we will be liberated, free from obstacles, something like that. I don’t remember the last part.

Also there is a similar quote by the great yogi Saraha, Naropa’s guru, who said, “We believe there’s something outside to be afraid of, but actually our concept is the one. What is frightening us is our concept, our superstition, there’s nothing outside of that. Our concept is frightening us.” There’s a whole quotation like that.

Before, a person was regarded as very harmful, an enemy, a very harmful person, but after meditating on patience and thinking of the kindness of that person—all the advantage, the benefit that we get from that person being angry with us and beating us or insulting or whatever they did to harm us; by thinking of all the benefit that we get from that—then that person becomes most precious. Think, “They are only benefiting me; they are most precious, the most kind one, our best friend.” So now here we totally change to the most positive, seeing them as our best friend, our best supporter, in order for us to have realizations and achieve enlightenment.

As I mentioned before, this afternoon as well, by putting a negative label then we see negative. By putting a negative label there’s the appearance of negative—we made the situation negative and then we see negative. Then there are bad feelings, negative effects—we generate negative thoughts toward other people.

Like that example, by putting a positive label on our problems—whether it’s abuse or whatever problem it is, such as having cancer, AIDS and so forth—then there’s happiness, enjoyment in the life. By putting a positive label and thinking of the benefits, those spiritual benefits, all the profit or benefits of having cancer, the benefits of having those sicknesses, by reflecting on the benefits of having the problem, then we see it as positive. If we put a positive label, then we see positive. Whatever problem we have, if somebody abuses us or whatever, then that makes us happy. The effect is happiness within us and there are positive thoughts toward others. We have a happy mind and positive thoughts toward others, opening our heart toward others.

However, here, whatever we see, whatever appears, all comes from our own mind, therefore we can change. It all comes from our own mind, therefore our mind can change and we can make our life a happy life. Instead of making our life miserable, with our mind we can make a happy life. We can make our life meaningful with our own mind, our way of thinking. Therefore we need a different way of thinking.

With peaceful, positive thoughts and a happy mind, that also results in a healthy body. Here what I was trying to say is that the negative interpretation, the negative label, results in a negative appearance, then we have negative, unpleasant feelings, we feel upset. When there is a negative label, a negative appearance, then we feel upset, we have unpleasant feelings. The label that we put on something affects us; the label that our mind puts on something affects us. This is the essence of what I was trying to explain, that it affects us. It upsets us and we have unpleasant feelings—not happy feelings, but unpleasant feelings. This makes our life unhappy. We have an unhappy mind, an angry mind, a depressed mind or self-centered mind, like this, then that makes others unhappy.

The other way, if we have a positive label there is a positive appearance and we have happy feelings, then we have a happy mind, a peaceful mind, and we are able to affect others’ happiness, so they also become like that.

In our daily life, every day, every hour, every minute, every moment, what kind of feeling we have—a sad mind or a happy mind—depends on what kind of label we are putting right now, at this moment. The effect of what label we put right now—happy or sad, positive or negative—in this moment, it’s totally related. As soon as we put a negative label, a negative appearance, then we have upset or unpleasant feelings. So today, within this hour, within this minute, within this moment, relating to what’s happening here, feeling sad or happy is the effect of whatever label we put on it. [Rinpoche snaps fingers] What label we put on it.

If we analyze, we can see this. Anybody can understand this by watching, by analyzing. Anyway, all these explanations don’t require faith in reincarnation or karma, all these things. It’s just dependent arising, just the effect, the consequences. Of course, there’s cause and effect within that. It’s not talking about karma, reincarnation, long-term, but just within this minute [Rinpoche snaps fingers] where our happiness, unhappiness, suffering, comes from, and how it’s affected by our concepts, by our labels. Whatever label we put and believe in, then that creates the concept. We put the label and believe in that, so that’s how we create the concept. Our concepts affect us; our concepts bring our life up or down. So depression comes from that.

The Twelve Links of Dependent Origination

The Buddha explained the twelve dependent-related limbs in the Rice Seedling Sutra. He explained ignorance, the twelve dependent-related limbs, the evolution of samsara, how we get reincarnated in samsara, the graduated entrance into samsara.

Ignorance is like the farmer who cultivates crops in the field. Then there is karmic formation or compounding action. Karma is like the field from which various crops grow. From karma come the various rebirths, such as a suffering rebirth, a happy rebirth, all these. Then there is consciousness, on which the compounding action leaves karmic imprints.

The consciousness, which carries the karmic imprints from life to life, is like a seed that is sown in the ground. By sowing one small seed, a huge tree trunk grows, with many thousands and thousands of branches and leaves. I’ve forgotten the name of the tree in India, the huge tree with many branches that cover many horse carriages. They put the carriages under the tree for its shade. I’ve forgotten what it’s called, anyway, that tree came from one small seed, then it grows huge like that, and it can give shade to five hundred horse carriages. It’s so huge. The consciousness is like the seed and from this the various experiences of karma—happiness and suffering—come.

Craving and grasping are like the minerals, earth, soil and water, then the seed which is ready to produce a sprout is like becoming. The karmic imprint left on the consciousness procrastinates and by craving and grasping it is made ready to bring its result, the next rebirth.

When the sprout comes, it’s like name and form. So now, after ignorance, craving and grasping and the two actions—compounding action and becoming—so after these three delusions and two actions, then seven results arise which are in the nature of suffering. So now, name and form: “name” is all the mental part, and “form” is the physical body. Then there are the six sense bases, then contact, feeling, and birth, old age and death. So where do all these seven results come from? They come from the consciousness. At this time, there are these seven results. Now what’s left is death. Old age already started in our mother’s womb, after the birth, so what’s left is only death.

These seven results all came from our own consciousness. Not only that, they came from the karma. All these results came from the intention, which exists accompanied by the consciousness. So all these seven results came from our own consciousness, they came from our karma, which is also our own mind, intention. Going back, all these seven results came from our own mind, the ignorance.

Not only that, everything came from the mind and we can relate this to the twelve links. Then in short, each day whatever view we have, each day whatever appearance we have around us—people being nice or negative, beautiful or ugly, dirty or clean, a beautiful flower or ugly flower, bad-tasting food or good-tasting food, bad sound or interesting sound, criticism or praise—so the whole world around us [came from the mind.] The appearances of the senses, what each of the senses sees, everything, whether it’s a living being or a non-living thing, the whole thing, including the weather, cold, hot, whatever appearance we have [came from the mind.] A beautiful mountain, an ugly mountain, the whole thing, whether it’s desert—not dessert that you eat after meal, of course, no question, that definitely has to come from the mind—or a beautiful mountain, the whole appearance around is, the view of our senses, all this came from our consciousness. I’m talking here about the twelve links.

Before I was talking about our immediate [reaction], how whatever we see [Rinpoche snaps fingers] comes from our immediate thought, from the thought labeling, depending on that, then how it affects us and makes our life happy or unhappy, all that. Here this is a long evolution, so where did all this come from? It came from the twelve dependent-related limbs, the consciousness. Because all this that we see around here every day, for example—whether it’s bad or good, whatever, food, sound, everything—all came from the imprints, it came from the consciousness. The imprints are left on the consciousness, so there are all these negative and positive imprints. From the negative imprints [we experience] ugly, bad sounds, ugly form, undesirable forms, tastes, tangible objects, and from the positive imprints [we experience] all these nice things regarding each object of the senses. So all this came from our consciousness, and not only that, all this came from our karma, compounding action, the intention, all this came from our intention. Then all this, now and even going back, came from our ignorance. So this is how things came from the mind.

This is one way of meditating on the twelve dependent-related limbs—not only the seven resultant sufferings which come from that, consciousness and karma, ignorance, not only that, but all these other things.

It’s very good to practice mindfulness of this. Actually you should spend days practicing mindfulness of the first one—how you see things in every moment. How things appear to you comes from how you label things in every moment, how your mind labels things. You can practice mindfulness of that all day—how everything comes from the mind in that way.

Then you can practice mindfulness or walking meditation this way, relating to the twelve dependent-related limbs, how everything comes from [the mind.] All these appearances of each of your senses, what you see, what each sense sees, all this came from your mind, consciousness, karma, ignorance. This is very, very good, very powerful meditation. It’s very good to practice mindfulness, to spend even one week just on that.

This is very, very good, a very powerful method for both sitting meditation and walking meditation. While you are doing walking meditation or while you are working, practice that mindfulness. So when you do that, suddenly if somebody gets upset with you or angry with you or has some problem, some obstacle or something happens, then it doesn’t bother you because you know this came from your own consciousness, your own karma, ignorance. But when you don’t think that, when you forget to think about it—even if you know it intellectually, but you forget to think about that—then you get angry. Why? Because the blame is on somebody else. The blame goes outside, on somebody else, so then you get angry. Then you engage in negative karma and harm the other sentient being.

In this way you come to realize what the Buddha said, that you are the creator. In this way you become the creator of your own happiness and suffering. It is up to you, it is up to your mind, therefore, you have all the freedom, you have all the choice. Instead of creating a problem, instead of producing suffering, you can produce happiness, right now. Instead of your life situation becoming a problem you can transform it into happiness. So you can change both things—right now and long-term. With a change of attitude you can produce happiness instead of suffering in the future.

Sorry, it took many ages, a long time. I think this is a very important meditation.

[End of discourse]