A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life

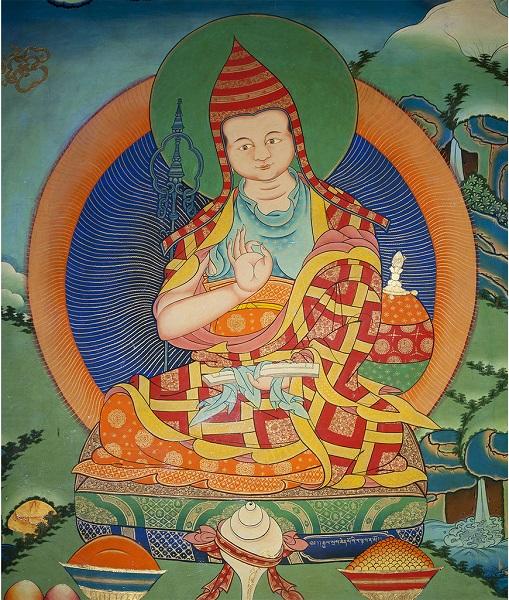

The great bodhisattva Shantideva is loved by all Buddhists, especially Tibetan Buddhists. His name, Shantideva, is Sanskrit. Shanti means “peace” and deva means “god.” He is renowned for his book, A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life (Skt: Bodhicaryavatara), the most beloved and treasured book for many Buddhist practitioners.

If we want to study and practice Mahayana Buddhism, Shantideva’s book is the perfect guide. It shows how to practice the most precious mind of bodhicitta and especially the six perfections that a bodhisattva, a being with bodhicitta, must practice to develop toward full enlightenment: the perfections of charity, patience, morality, perseverance, concentration and wisdom.

In the ninth chapter, the chapter on wisdom, Shantideva explains emptiness incredibly clearly, which means his book contains the key things we need to know to take us to enlightenment— bodhicitta and emptiness—and, as a bodhisattva, how to develop the qualities we need, such as generosity and patience. He shows us how to control our mind in order to destroy our selfish attitude and work only for others, the core of the bodhicitta teachings. He shows us how we must purify our delusions by confessing our negative karma and other purification practices, and how important concentration is in our practice.

Every word of this remarkable book leads us toward the wonderful mind of bodhicitta, the altruistic wish to attain complete enlightenment in order to best benefit all other sentient beings. There are so many people who have never even heard of bodhicitta let alone received teachings on it, but even just hearing the word “bodhicitta” brings huge benefit. It energizes and inspires us and strengthens our determination to work for others.

A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life therefore shows us how to control our mind and develop our altruism, and how to understand reality, the truth of how things exist. Without such vital elements, no matter what we do, it can never be effective in making us happy. No matter how much money or how many possessions or friends we have, we will never succeed while the mind is not imbued with compassion and wisdom. Our friends can’t guide us toward true happiness, but this book can. It’s the cure for all our mental ills.

The first chapter of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life is in praise of bodhicitta and shows us the benefits of realizing this precious mind. Like Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s text, the verses of this chapter are full of inspiration. In many of the meditation courses I taught in the seventies, I used verses from this chapter with a brief commentary to start the morning session as motivation for the day’s activities, hoping to inspire the students and show them how vital the mind of bodhicitta is. These motivational talks form the second part of this book.

I have received an oral commentary of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, but the first time I received it was from Khunu Lama Rinpoche, Tenzin Gyaltsen. This great bodhisattva pandit is inseparable from previous pandits such as Nagarjuna, Asanga and Shantideva.

SHANTIDEVA’S LIFE

A bodhisattva is a being who has bodhicitta, the mind determined to attain enlightenment for the sake of others. This is the sole determining factor for who is a bodhisattva. Wearing red robes and shaving the head doesn’t determine this, nor does all the book learning in the world. It’s the mind of enlightenment, that most amazing selfless wish to benefit others, that determines it. A bodhisattva can appear very ordinary and this was the case with Shantideva. When he first moved to the great monastic university of Nalanda, the other monks saw only a lazy person, utterly worthless, whereas he was already a bodhisattva.

Much has been written about this great bodhisattva. He had complete control over death and rebirth, completely the opposite to us ordinary beings who have no control at all. Every action of body, speech and mind was holy; there was not one thing he did that had even the slightest taste of self-cherishing. Every action, tiny and great, was done purely for others, to help release them from suffering.

Of the thousands of amazing pandits in the great monastic university of Nalanda he was peerless. He was a role model for anybody seeking the spiritual path. We should not only follow his advice in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life but we should see his remarkable qualities and how vital it is that we try to emulate him. We should learn about the way he led his life with such great compassion, with a well-subdued mind leading to actions of body and speech that were also well-subdued, doing only what was of benefit to others and never doing anything for his own sake. His only desire was to lead other beings to everlasting peace and because of that he never had a problem; there was not the slightest bit of confusion or agitation in his life. Problems arise from the unsubdued mind, the mind grasping at the self, and when that is transcended, problems are transcended. The three poisons of ignorance, attachment and anger are destroyed in a being such as Shantideva because the egocentric mind, the self-cherishing thought, has been overcome.

We need to know it is possible to overcome egoistic concerns and we need guidance on how to do it, therefore we need beings like Shantideva. Like the Buddha, he is a teacher we can trust and an ideal we can look up to. We can’t become completely like him immediately, but we can see that as we develop qualities such as compassion and equanimity, our self-cherishing diminishes and our problems lessen. Just as scrubbing a filthy pot takes many attempts and a lot of effort, scrubbing the mind of its delusions is a long-term job, a job that will probably take lifetimes. We need a long-term view and the inspiration that teachers and yogis like Shantideva can give us.

In the early 1970s, when I first started teaching Western students in Nepal, many people came in search of something more than the unfulfilling material riches of the West. They had read the biographies of the great yogis like Milarepa and Naropa and they wanted that simplicity and purity. Many found the actuality of developing the mind harder than they had thought and dropped out, but many stayed and turned their lives completely around. They saw that within the teachings and within the examples set by these great yogis was everything they needed to take them all the way, not just to the complete peace of nirvana, but to full enlightenment, the mind that is fully awakened and only working to benefit all other sentient beings.

It’s very interesting to see how the great beings such as Shantideva achieved enlightenment, and in doing so we see that we too can achieve it. It’s definitely possible to transcend the petty concerns of this life and go on to attain the various realizations that are necessary on the path to becoming fully awakened. But it’s not easy. We need strong determination, and that will only come when we can see the vital need for turning our backs on selfish concern and our confused, deluded way of thinking, and see what an incredible opportunity we have if we can persevere. At present, we admire and emulate worldly role models, such as rich businessmen and rock stars, the glamorous and influential, and because of that we trap ourselves more and more in the quagmire of samsara. Now, we need to change our role models to the truly admirable beings. We have living examples in beings like His Holiness the Dalai Lama and we have the examples that have inspired people for thousands of years, like the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, and the great yogis like Shantideva and Milarepa.

Shantideva was born in the eighth century CE in India, near Bodhgaya, where the Buddha was enlightened.21 He was highly intelligent. When he was six he meditated on Manjushri. Because Manjushri is the manifestation of all the buddhas’ wisdom, meditating on him is a very quick method to realize the absolute nature of things, emptiness. There are many stories of meditators in India and Tibet who have gained realizations of emptiness through meditating on Manjushri. When he was as young as six, Shantideva not only saw Manjushri but had a realization of him. Manjushri himself gave the young Shantideva many teachings, passing down the lineage of the profound path—the wisdom teachings—to him.

Shantideva was a prince, and after his father died the people asked Shantideva to become the king. Shantideva could not refuse the people and had to promise to become the king, but the night before the inauguration he had a dream. Manjushri was sitting on the king’s throne and said to Shantideva, “The one son, this is my seat and I am your guru, leading you to enlightenment. We can’t both sit on the same seat.” When he awoke from the dream he realized that he could not accept the crown, that he should not enjoy the possessions of the king or live like a king.22

He escaped and went to Nalanda, where the abbot ordained him, naming him Shantideva. For a long time he received extensive teachings on sutra and tantra from both the abbot and Manjushri. Although inwardly he was studying very hard and having realizations, externally he didn’t appear to be doing anything. He also secretly composed two texts, The Training Anthology of Shantideva and the Compendium of Sutras.23

Nalanda was a vast and wonderful place, the greatest seat of Buddhist knowledge in the world. Thousands of scholars studied, debated and meditated there, not just normal students, but great pandits, whose inner knowledge of Buddhadharma gained them profound realizations. They wrote great treatises and developed incredible tenets on logic, as well as studying the sciences, art, medicine and so forth. I can imagine that Nalanda was a very busy and vibrant place, and yet, outwardly, Shantideva appeared to do absolutely nothing. He seemed a very lazy scholar. While the other monks studied, debated, prayed, did prostrations, engaged in debates and did all the jobs around the monastery that were needed, Shantideva appeared to do none of these. The other monks could see none of his inner qualities and they became quite contemptuous of him, calling him bhusuku, the “three recognitions,” which means eating (bhu), sleeping (su) and making kaka and pipi (ku), the only things they ever saw him do.

In fact, Shantideva was a hidden yogi, who already had great qualities. He was what is called kusali, which means having virtue; when it is used for a person it means one who does only virtuous actions but doesn’t show virtue on the outside. Shantideva is invariably used as the prime example of this.

It appeared to many people that my guru Lama Yeshe, who is kinder than the three times’ buddhas, was always busy doing things and enjoying himself and that he didn’t meditate. They didn’t see any external signs of meditating such as physically sitting in meditation posture. Many people thought Lama was very worldly. They didn’t recognize his inner practice, his inner realizations, but just judged him from the outside, from what they saw with their eyes. They didn’t know that Lama was a great yogi who had very high tantric realizations, completion stage realizations, and freedom from birth and death. Lama could not be overwhelmed by samsara. He enjoyed sense pleasures without the shortcomings of samsara; he enjoyed them purely for the sake of other sentient beings, to benefit other sentient beings, without being overwhelmed by disturbing thoughts, by the three poisonous minds. Lama actually meditated all the time. People used to think that Lama, who was in constant meditation, was not meditating and that I, who never meditate, was meditating.

A kusali never shows on the outside that he is learned and has attainments; he doesn’t do prostrations, make offerings or show anything like this. But he is accumulating extensive merit mentally by doing the practice of offering himself to the holy objects and making charity of himself to the sentient beings.

The other monks thought Shantideva was completely foolish and had no place at Nalanda. The Sangha—monks and nuns—are supposed to listen to Dharma subjects to repay the offering of the robes that people give them. The monks thought that he was just wasting the benefactors’ offerings, which is the cause of much negative karma, and that he should be expelled, but because that was difficult unless somebody did something criminal or extremely outlandish, they devised a trick to get him out. In the monasteries, the monks had to memorize many texts on both philosophy and monastic discipline, which they were then supposed to recite publicly by heart in the prayer hall. The other monks believed that Shantideva had not memorized anything, so they decided to invite him to recite a sutra teaching. They thought he would disgrace himself and would then be forced to leave the monastery.

The monks built a really high throne without any steps for the occasion, convinced that Shantideva would run away when he saw it. However, when he arrived, in front of the whole monastery, he asked whether they wanted him to recite a text from Shakyamuni Buddha or something not given before. Of course, the monks wanted something new to really embarrass him.

Suddenly he was there on the throne and nobody knew how he got there.24 Then he started reciting the complete Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life from memory, like water pouring from a clear spring. In one session, without break, chapter by chapter, he explained perfectly and succinctly each of the six perfections of the bodhisattva’s actions. When he reached the ninth chapter, the chapter on wisdom, he suddenly flew up from the throne, flying higher and higher until he appeared no bigger than a fly, and then he disappeared altogether. But the monks could still hear him teaching perfectly, as if he were still on the throne.

Needless to say, the monks were completely shocked at this amazing event. They had no idea he was a hidden yogi, a great bodhisattva and a holy person with great attainment of high realizations. The teachings he gave had a profound effect on them. Those with heresy toward Shantideva developed great devotion. This was why he did what he did. A hidden yogi almost never displays his power, but Shantideva could see that this was what the Nalanda monks needed.

After that, he lived at Nalanda with great respect from the other monks. He also traveled and there are stories about him. In Magadha,25 one of sixteen great kingdoms of ancient India, he became a servant to a group of five hundred people who held wrong beliefs. Once there was a terrible storm lasting many days and their food ran out. They were suffering so much and arguing with each other, saying that whoever went out to find food for them would be their leader and they would follow him. Shantideva, as their servant, went out to beg and returned with one bowl of rice. However, when he shared it among the five hundred it satisfied them all. In that way, he showed them that their beliefs were wrong and they willingly accepted what he taught them.

Also at that time there were about a thousand beggars suffering and near death because of a great famine. Through his psychic powers, Shantideva was first able to help them and then show them the teachings and lead them to perfect peace.

On another occasion, he was staying near the palace of the king of Arivishana. The palace was attacked by a group of cruel people intent on stealing the king’s possessions, but Shantideva promised to protect the king and his people, and was able to control the bandits. The peace and prosperity that Shantideva brought to the land and the people made a powerful person jealous and he took the king aside, saying that Shantideva was cunning and would deceive the king. As proof he said Shantideva had defended the territory with a wooden sword, showing it was obviously a trick.

That made the king angry and he demanded that Shantideva show him his sword. Shantideva didn’t want to, saying that seeing the sword would harm the king, but the king insisted, even if he was harmed. So, Shantideva asked the king to cover one of his eyes and he pulled the sword from the scabbard. It was wooden, but it gave off such a brilliant light that the king’s eye that was open was blinded. He was terribly upset that he had doubted Shantideva and he apologized, taking refuge in Shantideva and taking teachings from him. In that way, Shantideva led him on the Dharma path. The sole reason Shantideva had gone to live in that kingdom was for this to happen.

After that he went south to Glorious Mountain, where there was a Hindu teacher called Shankaradeva who held wrong beliefs. Supported by the king, he debated with Buddhist pandits, not only debating with words but also with psychic powers. He made bets with his opponents, saying whoever lost the competitions would have their temple burnt down. Nobody could compete with Shankaradeva but Shantideva challenged him. During the competition, the Hindu teacher created a mandala of Maheshvara, their god, in space. Shantideva remained in the wind concentration, prana, and all of a sudden a heavy storm happened, blowing the entire mandala away. As a result, Shankaradeva lost, and since even with his psychic powers he could not compete with Shantideva, he and many of his followers became followers of the Buddhadharma and helped to develop the teachings.26

Shantideva was once like us, but he worked on his mind until he became completely free from delusions. Therefore, he is a great inspiration. There have been many yogis who have done this. What makes him incredibly special for us, however, is his book, A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. Not only does it lay out everything we need to do to become enlightened, it does so in language that is beautiful and simple. It’s a book that has inspired countless people since it was written over thirteen hundred years ago. It tells us that we too can develop our mind to the levels of realizations that the great masters have attained and shows us how to do it.

NOTES

21 Ringu Tulku’s online biography of Shantideva says he was born in south India (some sources cite Saurastra in Gujarat) to King Kalyanavarnam. He was given the name Shantivarnam. Alan Wallace’s introduction to Shantideva’s Guide (p. 11) says, according to the 16th century scholar Taranatha, like the Buddha he was born into a royal family but on the verge of his coronation Manjushri and Tara appeared to him and urged him not to accept the throne, so he left the kingdom and retreated in the wilderness, attaining siddhis. [Return to text]

22 In another version, Rinpoche says Shantideva married a girl called Tara and when he realized he couldn’t live with her he accepted being thrown into the river in a box, and thus escaped. [Return to text]

23 Whereas The Training Anthology (Skt: Siksasamucchaya) is still extant, Compendium of Sutras (Skt: Sutrasamucchaya) is no longer available in any translation. [Return to text]

24 In another version Rinpoche says that he placed his hand on the throne and gradually pulled it down until he could easily get onto it. [Return to text]

25 The capital of Magadha was Rajagriha (Rajgir), where the Buddha gave the Prajnaparamita teachings. The Buddha spent most of his life in Magadha, which is situated in present-day Bihar. [Return to text]

26 See The Nectar of Manjushri’s Speech, pp. 20–21, and Butön’s History of Buddhism, pp. 260–61, for more details of these stories. [Return to text]