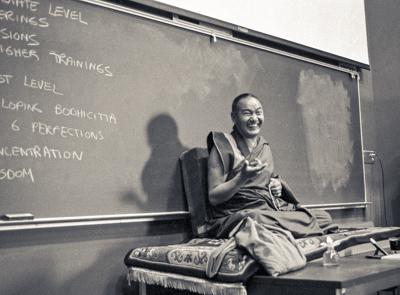

University of California, Santa Cruz, 23 July 19837

Good evening, everybody. Tonight, I’m supposed to talk on the subject of anxiety in the nuclear age. And, of course, there are indeed reasons to feel anxious about the prospect of nuclear war. Most of you know this already.

Now, when we talk about nuclear war, we’re not just talking about bloodshed, the killing of people. I heard that in America tens of thousands of people die on the roads every year. That looks like a tremendous number of people, and it is, but when it comes to nuclear war, that’s much more dangerous; it’s very serious. A nuclear explosion can release millions of tons of energy. For example, if the Soviet Union were to fire a nuclear missile into the center of San Francisco, the effect would be felt for hundreds of miles in every direction and millions of people could be killed or seriously injured. Medically it would an almost impossible situation to deal with, and a vast area would be left uninhabitable for a very long time. It would be an environmental catastrophe. The after-effects on just the human population are too terrible to even contemplate. So, people have good reason to be concerned, fearful and anxious. I understand that. The potential for all this to happen does exist.

However, from the Buddhist point of view, nuclear war has an evolution and we have explanations as to how and why it exists. Simply put, we can talk about internal nuclear war and external nuclear war. The internal aspect addresses why such weapons have been made—people’s motivation for making them. Before nuclear missiles existed, the human mind speculated and projected in that direction. People were serious; these kinds of weapon were not a joke. People wondered, “How can we protect ourselves? What sort of equipment do we need in order to win a war?”

According to the Buddhist point of view, or my point of view at least, when people started speculating like that, creating nuclear weapons in their imagination, nuclear war had already started; consciously or unconsciously, internal nuclear war had already begun.

Then military experts began pushing for the creation of such weapons, explaining to politicians why there was a defensive need for them, and thus the arms race began. In America, people tend to blame the president for escalating the arms race but in my superficial view, I don’t think he’s primarily responsible. There are people behind him, those who feel responsible for the country’s peace and freedom, such as the army generals, pushing the president, saying things like, “If we don’t have these weapons, we can’t guarantee that we can do our jobs.” I’m sure you know all this already, but be careful who you blame for what. You have to analyze things carefully and truthfully.

We all say that we dislike harming others and try to protest the development of nuclear and other weapons, but it’s already reached beyond our control. Even though we mean well when we protest and do many other things to try to stop the production of nuclear energy, it’s too late. It’s not worthwhile. It doesn’t matter. They’re going to produce nuclear power and weapons anyway. All these things will keep popping up like mushrooms.

What we can do, however, is try to educate people not to use nuclear energy in a harmful way. That is something we can do. Undertaking unreasonable actions will not produce the desired result. It’s difficult. The fact is that nuclear energy is here to stay; it’s a reality. So the best we can do now is to understand the dangers of nuclear war and try to educate people as to those and turn them against the use of nuclear weapons. That, I think, is our responsibility.

Just being anxious and fearful is not going to help. That cannot stop the problem. Furthermore, the anxious, emotional, disturbed mind within you is also highly destructive. What it produces is hatred, and that itself is an internal nuclear war. So that’s what I’m saying. When you harbor hatred, you’re waging an internal nuclear war, whether you’re aware of it or not, and in that way, nuclear war has already begun to manifest in the world.

From there, it then appears in your speech, when you start to discuss fighting. Just listen to the radio; you can see. You don’t need any higher education. Of course, this is just my observation. I’ve listened to Russian radio; I’ve listened to American radio. That’s been enough. You can feel the vibration. So war is there, in thought and speech. What hasn’t manifested yet is physical war, the expression of that thought and speech. So how do we control the physical use of nuclear weapons?

From the Buddhist point of view, it’s the mind that has to be controlled. Therefore, we have to educate people as to how to control their mind. People have to guarantee not to touch weapons or harm others. Otherwise, how can these things be stopped?

We all have knives. There are knives in every home, every kitchen. Potentially, we could already be killing each other. We’re all armed. What stops us from using those knives to kill other people is control; control of the mind. Since hatred is the real, internal nuclear weapon and manifests externally as physical war, we need to eliminate hatred as much as we can.

If we check up honestly where our anxiety comes from, we’ll find that “I’m scared of this, I’m scared of that” boils down to “I’m scared; I’m scared.” We’re projecting ourselves as something very concrete: the self-notion; the self-concrete self-entity. The me is afraid; the me is the most important thing; the me should not be harmed by nuclear arms. Buddhism would call this basic thinking the selfish attitude, self-cherishing, and the result of following it is always restlessness and misery.

So basically, anxiety manifests from the ego and the notion we have of ourselves as something concrete; an unrealistic projection of what we are. That is the cause of anxiety. There is no such thing as the concrete concept we have of ourselves. Inwardly, externally, it is totally nonexistent. It’s only a projection. If we could only recognize that, we’d be able to relax and all our anxiety would be eliminated.

The Buddhist point of view is that human beings should be as peaceful and happy as possible, and we ourselves are responsible for making that happen. We can’t blame God for the problem of nuclear war; we can’t blame Buddha either. We human beings are responsible for both our happiness and our misery.

The cause of anxiety, therefore, is the selfish attitude, the egotistic mind, and we have to recognize that within ourselves there is no concretely existent I; the subject, I, does not exist. Anywhere. It’s only a projection, a hallucination. If we recognize that, we’ll relax. Anxiety derives from the overestimated projection of oneself. It’s not realistic. It doesn’t even touch reality.

Let’s say I cry. You’re watching me crying, “I’m scared of nuclear war.” I’m crying with anxiety; what can you do? You’re going to say, “Please don’t worry. Nothing’s going to happen for at least two weeks. At least enjoy yourself for that time.” It’s true; worrying is a waste of time. They’re producing nuclear energy twenty-four hours a day. So you should enjoy your life; relax. The selfish attitude produces anxiety, fear and aggression. It’s not a relaxed mind; it doesn’t produce peace.

The point is, now, bringing peace to the world is an individual responsibility. If, as individuals, we were all to develop such a responsible attitude and behave accordingly, that would bring about world peace. So what we can do is to educate people through our actions. We have the capacity to control our hatred and the actions that ensue from that negative mind. Each of us has the universal responsibility of bringing peace to our own mind and to those of others.

That way of thinking is not anxiety. It comes from having a broad view, broad universal concepts, so that our heart is opened. Negative emotions make us tight, twisted and nervous, and that produces hatred. If we can trust ourselves never to touch nuclear weapons, never to touch any weapons to kill other people, from the Buddhist point of view, that’s an incredible achievement. But this has to be a conscious, verbalized determination and not just an easygoing, “Yeah, I won’t be touching lethal weapons; I have no desire to.” Because when the actual situation arises, we’re going to be thinking, “Me, me, me, me, me. I’m the most important one. I’m the self-existent, concrete one. I’m going to kill him before he can kill me.” If you have that kind of attitude, your musing that you won’t touch lethal weapons is a joke. It’s just hypocritical.

There once was a monk who was threatened by another man. The monk said, “I’m not going to kill you. Your killing me is your choice. That’s your business.” That’s the kind of brave mind we need. But we’re so superficial. We’re like, “La, la, la, la, la. I shouldn’t kill. I don’t want to harm others. I’m peaceful.” But when it comes to the crunch, you’re going to reach for a weapon. I’ve seen this happen myself. People live peacefully and exhibit compassion, but when a life--threatening situation arises, they’re the first to reach for a weapon.

Therefore, it’s important to give yourself an injection of determination every day: “I’m never going to touch weapons to kill other human beings.” If you then take responsibility to act accordingly, I think that’s really great. And if you then pass that peaceful action on to the next generation, and they to the next, I think we can have hope for the future.

So now we know that emotional fear basically comes from the selfish attitude that arises from projecting one’s self as an unrealistic entity. That’s where fear comes from. If we did not harbor a selfish attitude, there’d be no reason for us to experience emotional fear. We also know how nuclear weapons function and how individual people guaranteeing not to use them can stop their deployment.

However, these days many nuclear weapons are controlled by machines. If the machine makes a mistake, the weapon is launched. Therefore, we have to take control of nuclear weapons away from machines and, in addition, put an end to the arms race. And the best way to reach those goals is through education.

That doesn’t mean asking people to become religious or indoctrinating them or getting them to become some kind of philosopher. It just means getting people to simply be human beings. Just being human is enough. Whether you’re a capitalist, a communist or neither, anybody who deeply understands the dangers of a nuclear confrontation is going to say, “I’m never going to touch such weapons.” Enough people saying that is the way to guarantee there will not be a nuclear war. To educate others, to get them to commit to abandoning the use of nuclear weapons, we have to be certain that we ourselves are not going to use them. That’s the most important thing.

Buddhism’s main concern is that human problems are created by the human mind. Evil actions come from evil thought, evil thinking, wrong thinking. That is the source of all misery. However, we have the capacity and power to extinguish wrong thinking. We call that liberation. All of us can do it.

Therefore, worry is illogical. It never stops problems; it doesn’t change anything. We worry about nuclear missiles. They’re always there: on the land; in the ocean. Even if we were to pray to God or Buddha for them not to be, they’re there. They already exist.

But still, I’m optimistic. We’re human, and, speaking for myself, we like living, we’re attached to ourselves and we’re afraid of death. Therefore, as educated people, we understand that bringing death and destruction to other people is not good. Of course, we all have to die, but we should all have the chance to die peacefully, and we should leave a suitable environment for the next generation to live in.

Buddhism always talks about loving kindness. That means not only not killing others but also not harming them in any other way as well. We should ask ourselves, do we have the attitude of loving kindness, which is the guarantee not to harm, not to use nuclear weapons? Loving kindness is the universal understanding that all beings on earth are suffering—with anxiety over nuclear weapons and, in general, with fear about losing their life in so many other ways. There are so many ways in which we are scared of destructive forces and by the lack of fulfillment in finding happiness.

And we are all equal in this. All humans are equal in desiring happiness and freedom from suffering, yet they always end up in miserable situations with fear and anxiety. Therefore, we should generate compassion for all of humanity, although politicians might find this difficult since they already feel, “These people are the enemy. We have to kill them.” As long as someone designates someone else as an enemy, they’re already committed to harming that person. Thus it’s important to understand that there is no external enemy. The real enemy is wrong thinking, which leads to anxiety and dissatisfaction. That is the true enemy. The good thing is that we have the power to change our mind, to go beyond dissatisfaction and anxiety.

How many of you here today think you want control and are prepared to make the determination, “From now on, for the rest of my life, I’m never going to touch any weapon with the intention of killing another human being”? I would like to know. Then we will see. [Most people raise their hand.] Oh! Grateful! Thank you so much. We’re telling the truth. We’re not hypocritical. We are concerned; we act. That’s wonderful. The people of this country are amazing. So sincere, so honest, so prepared to act. That’s great; it makes me very happy.

Even in Buddhist countries some people find it difficult to say, “I’ll never kill anybody,” because they still have the attitude, “I’m not sure. Maybe a thief will enter my house and try to kill me, so perhaps I’ll have to kill him in self--defense.” Others may be thinking, “Perhaps foreign invaders will take over my country and I might have to kill in order to defend it.” Even in Buddhist countries it can be difficult for some people to make the kind of determination you have just made: “I’m not going to touch weapons to kill any human being.” It’s absolutely rare that people can make that promise; it’s very rare, I tell you.

This is not a pledge made out of some kind of religious conviction, either. It involves something else—thinking in another dimension. “I’m not going to touch weapons to kill people” is not a religious vow. Nonreligious people can make this determination too, out of sympathy for other human beings. I think it’s a very reasonable thing to ask. We’re not fanatically asking others to become Buddhists or Christians. We don’t care. Personally, I don’t care. What’s amazing is that whether you are religious or nonreligious, you understand the basic human qualities and have the dedicated attitude to serve humankind. What more can Buddhism add to that? I don’t think we have anything else.

We call people who have that attitude bodhisattvas. That’s the term we could use, but we don’t need terminology. Just dwelling in that attitude is enough. Really. In Buddhism we say that we prostrate to those who are dedicated to not harming others but serving them instead. Such people are representatives of the universal being. We believe that. Such people are great. Even if you are small, from the Buddhist point of view, you are a universal entity taking universal responsibility. That’s tremendous.

Thank you so much, and I congratulate you. I’m grateful that in this culture, people can think this way. It amazes me. I truly believe that in this world, as long as we are human, we can understand each other, what our needs are, what should be avoided, and what should be abandoned for the sake of others. I am really confident that we understand each other.

I don’t need to tell you anything else because we are communicating well, heart to heart. And we are taking responsibility for controlling the actions of our body and mind. What more can we ask? Even if Buddha or Jesus were to come here, they couldn’t ask for more than that. Thank you so much. I don’t have anything to add. But if you have any questions, you’re welcome to ask.

Q. I certainly have a concerned attitude, but I also have much fear when I think of the great suffering that would come to all others, animal and human, in a nuclear war and the end of this rare and beautiful planet for future beings. What thought counteracts this second fear?

Lama. Well, when we use the word “fear,” we have to remember its different dimensions. There’s emotional fear, when we understand that some kind of situation has arisen or may arise. But then there’s fear based on concern for others and the harm they may experience through the use of, say, nuclear weapons. In my opinion, that’s not emotional fear. That’s fear derived from comprehending wisdom—wisdom that comprehends the universal reality of all human beings and human need. From a Buddhist perspective, perhaps you can call it fear, but it’s not negative fear; it’s not destructive fear. It’s an understanding that produces peace and love.

Q. When we feel anger what should we do? Repress it, show it if it’s not harmful to others, or ignore it?

Lama. If somebody makes you angry, the simple thing is to analyze the situation. First analyze what caused the situation to arise and what effect it’s having. When you analyze the way in which anger projects its object, you can see that it’s exaggerated; it’s too big. Anger sees something concrete there, but when you investigate the object in detail—what it is, how it appears, what happened—you can’t find a concrete object of anger anywhere. That’s one way of eliminating anger.

You can also think about whether hanging on to this object of anger is worthwhile or not. The moment you conclude that it’s not, that it’s destructive to both yourself and others, you can change your mind. By thinking that it’s not worth keeping, you can let it go. If you keep the conversation going, constantly thinking, “He did this; she did that; he did that; she did this,” you’re just perpetuating conflict and restlessness in your mind. It’s not worthwhile.

You can also damage or eliminate anger intellectually by analyzing its evolution. You can discover how ridiculous it is. Take a family argument, for example. You put a vase of flowers here. Then someone comes in and says, “Why did you put those there? They go here.” You respond, “No! I want them here!” And so it goes, back and forth, fighting each other over something so unimportant and small. There’s no big reason. It’s simply not accepting transitory change. That’s what’s making you angry. When you analyze, you see that change is the nature of things. Someone wants to move the flowers from here to there? Let go. Wherever they are, you can still survive.

We often get angry because we think unimportant things are important and we strongly resist change, as in the example. That’s wrong. As you know, Buddhism always emphasizes impermanence. Change is natural. It has nothing to do with concepts. You plant seeds; flowers grow. You put them in a vase; they perish and die. Changing, manifesting in different ways is what inevitably happens. It’s natural.

Once we were babies. Then we got bigger and bigger and bigger and now we’re going gray and getting ready to die. Change is natural. Wives change; husbands change; girlfriends change; boyfriends change. It’s all natural.

So it’s very important that we accept change as natural. We should respect the nature of things. Getting angry with others means we don’t respect them. Someone wants to move something from here to there, we want it left where it is and get angry at that person. That means we’re disrespecting the other person’s will and the process of change.

And especially, anger is the worst negativity. Lord Buddha explained that anger is the most concrete negativity. It’s always negative; there’s no exception. Why is that? The minute anger enters your mind, you become dark, like a thundercloud, and manifest to others in that way. There’s no exception.

Buddhism does make an exception for desire. Desire, attachment, is usually negative, but it can be positive. There’s a way you can use it to bring peace and positive results. Anger can never be used that way, so anger is our worst enemy. We should abandon anger as much as we possibly can. At least we should try to do so. Trying is good enough. We need to understand, “Anger is destructive. It destroys my peace; it destroys my pleasure. It destroys my companions and other people as well. The most important thing I can do in my life is control my anger.”

Before I was talking about the point of view of the object of anger. We can also analyze the subject, the angry person. This morning, when everything was OK, he appeared so handsome and nice. But this afternoon, now that he’s angry, he looks like a monster: angry; ugly. That’s how anger can change a person’s appearance. This morning he was so holy and dear. Now he’s become completely evil. Of course, that’s not really possible, but in my perception, to my exaggerated projection, it seems to have happened. From the side of the object, change is natural, but not radical change. But to my radical mind, such profound change in appearance is possible. And I think that Western science now agrees that the way we see things is according to our projection, which is similar to how Buddhism explains reality.

Q. What about killing to preserve the lives of other beings? Is it ever acceptable to kill in order to save others?

Lama. That’s a very dangerous question. I want you to listen very carefully to my reply so that you don’t misunderstand what I say. Let’s say I have a nuclear weapon and am planning to blow up New York City and kill millions of people and you know clean clear that this is my intention. I think it would be all right if, out of great love, great compassion and great wisdom, you were to kill me. Why? Because you’d be doing it for the sake of all those people whose lives I’d have destroyed.

This question is similar to what several of my medical doctor students have asked me. Some of them have been disturbed because they have had to kill rats and monkeys in medical experiments; they know Buddhists aren’t supposed to kill any living being. I have to answer, don’t I? I can’t ignore them. So I say, “Well, as long as your research will benefit humankind and even animals as well, I guess experimenting on and killing one monkey might be OK.”

The point is, if you have great compassion and a clear understanding of what benefits the majority, perhaps there can be exceptions. But still, I have some doubt. If our understanding is limited, we can easily make mistakes. Therefore, exceptions to the Buddha’s injunction not to kill would be extremely rare.

Q. How should we deal with people who consider us as their enemies or those who don’t trust us?

Lama. With compassion—according to the way I was educated, people who hate you are objects of love and compassion. Why? Because they are not enemies forever; tomorrow they can become friends. There’s no such thing as a permanent, self-existent, concrete enemy.

We should know from our own experience that things always change. Today somebody can be a dear friend, tomorrow an enemy. Who knows? It’s all so relative, but so common—look at how many marriages break up, with people who were once loving partners regarding each other as mortal enemies. Before, they couldn’t bear to be apart; now they can’t stand the sight of each other.

Therefore, I think it’s important to deeply imprint your mind with the knowledge that there’s no external enemy, so that if one appears to manifest today you don’t get caught up in hatred and just let go, thinking, “By hating me he’s hurting himself; he’s suffering. What is it in me that upsets him so much?” Do you see Buddhism’s reverse thinking? We think there’s some kind of destructive vibration in me that makes him hate me. I’m actually responsible for others not liking me. This is opposite to what we normally think; we think the hurt inflicted on us by our enemy is his fault.

Lord Buddha’s psychology is that we have some kind of negative magnetic energy within us that stimulates anger to manifest in another person, who we then label “enemy.” Controlling that energy within us is the best way to eliminate enemies. From the Buddhist point of view, seeing others as enemies and wanting to destroy them is completely wrong.

The great bodhisattva Shantideva said that if the entire ground is covered in thorns, it’s easier to avoid getting stuck by putting on shoes than by covering the ground with leather. Wearing shoes has the same effect as covering the whole earth with leather. Similarly, if we control our anger with patience, no external enemy can be found. Our main enemy is within; that’s the one we have to conquer. If you try to destroy external enemies, how far can you get? Maybe you can kill one or two people, but more enemies will arise. You can’t get rid of enemies that way. But if you get rid of the mind that sees enemies, no further enemies will ever be seen.

Q. You have spoken about overcoming the fear of death. My brother, who is 72 years old, has just learned that he has only a few months to live. How can I help him overcome his fear of death?

Lama. My way is sort of simple. You can tell him, “You’ve been successful. For more than seventy years you’ve had a good, enjoyable life. Now, remembering that, you can die happily and peacefully. You don’t have to worry about me or your other family members. Accept what is happening and relax.” Teach him relaxation meditation. Also teach him that death has been part of the natural evolution of life for as long as humans have existed. Therefore, he should not worry. Furthermore, if he is relaxed at the time of death, it can be a blissful experience rather than a fearful one.

So, you can explain all this to him. Even if he’s a nonbeliever, nonreligious, you can explain that peace is within him and that it can guide him. If he’s a Christian, explain in the Christian way that God will take care of him and liberate him into eternal peace. Use the right psychology according to his background. This is the way to help him. What you should not do is tell him something that he doesn’t believe. What you say should be oriented to his way of thinking, something that he can understand.

The important thing to convey is that death is not something horrible and painful. It’s not. Sometimes we look at it as painful, but it can be completely blissful. Therefore, he shouldn’t worry.

Anyway, we’ve been destined to die ever since we were born, so worry won’t help. And as long as his mind can still understand things, you can tell him that it’s tricky—many of the things that manifest to the mind at this time are simply hallucinations, not a true picture of either inner or outer reality. They’re a result of wrong thinking, wrong projections. Knowing that can allay all fear. Believing the concrete vision of what we see to be real can be a source of confusion and misery. Death is not something to fear. It is something we can understand, comprehend, work with and control. That’s possible.

Q. How can nonviolence bring peace to the people of El Salvador?

Lama. That’s a good question. Now I have to study politics again! Well, that’s a good, practical question. First, we have to analyze what the problem in El Salvador is. Once we determine that, we should ask, is adding war to that a solution or something else? Analyze the situation. All conventional phenomena are relative and changeable, so we should analyze how we can change it for the better. If we find there’s a way, we should act upon it. War is not necessarily the answer. All problems have a root—that’s what we have to determine and try to change, rather than fight. However, I don’t know what the root of the conflict in El Salvador is. I can give a theoretical answer but that may not apply in this case. I mean, theoretically I can say that war results from self-cherishing. People fight because they’re afraid of losing their material possessions, their power and so forth, so they keep fighting each other. That is universally understandable. But how to implement this understanding, how to call a truce? That I don’t know. I’d have to do more analysis in order to find a real answer, an answer to the situation that does not involve bloodshed and killing. But it should be possible.

Q. What is the best way to benefit others most effectively?

Lama. That’s simple. First, instead of being a disaster, get yourself together. What I mean by getting yourself together is taking care of your own moral conduct, your own psychology and your own material situation. Show yourself in a good light. That’s the way to help others. Live right. Just your living right helps others. That’s all. It’s very simple. But maybe some people don’t know, so I have to tell you.

Often, we’re too ambitious: “I want to help others. Can you give me something to do? I want to help you.” I’m a bit doubtful about that approach. Wherever you are, just be. If a situation arises where you can be of help, do what you can for others. Just by being available, you’re serving others. There are, of course, many ways in which we can help others. You get the general idea, but there can be many detailed explanations.

Take, for example, a couple living together. How do they help one another? By getting their own life together. They share a house and each person takes responsibility for helping the other by being strong. If one is always crying, “Blah, blah, blah, you were not nice to me yesterday,” over some tiny issue, like the example before of moving a flower vase, that person is not together. And part of that is a lack of awareness of their own disorderly thinking and wrong actions. Like, say I’m the husband and I put the flowers here. My wife can’t deal with that: “What a slob. He has no concept of beauty. Anyway, he’s ugly, so his actions are always ugly.”

In that case, neither person is together. “Together” means acting reasonably, sensibly, and not being a baby: “If I act like a baby, my wife can’t take it.” That means I’m not together, not reasonable. So just be sensible and together so that your partner can be proud of you. That’s the way to help your spouse; just giving them chocolate doesn’t really help.

Well, I think that’s all we have time for. Thank you so much, everybody, especially the Oakes College people who worked so hard to put this evening together.

7 This public lecture is available as a DVD and on the LYWA YouTube channel. [Return to text]